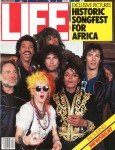

We Are The World

HISTORIC SONGFEST: A REVEL WITH A CAUSE

HISTORIC SONGFEST: A REVEL WITH A CAUSELife

April 1985

Note: A longer, fuller version treatment of this story can be found under the BOOKS heading: WE ARE THE WORLD: The Photos, Music, and Inside Story of One of the Most Historic Events in American Popular Music.

At two in the morning, Ray Charles strolls out of the studio for a moment, claiming he’s had no good lovin’ since January. (Of course, it is January.) Cyndi Lauper bops off to fix her makeup. Michael Jackson and Paul Simon, both certified wallflowers, huddle behind a potted plant to discuss songwriting. At the piano sits Stevie Wonder, noodling. Willie Nelson asks Bob Dylan if he plays golf. Dylan, slightly amused, replies, “No, I’ve heard you had to study it.” Says Willie, who has become obsessed by the game, “You can’t think of hardly anything else.” Across the room Bob Geldof, organizer of Britain’s Band Aid project, which raised millions for famine relief, passionately explains to Bruce Springsteen the logistical difficulties as he draws a map of Africa on a piece of sheet music.

Welcome to a relatively quiet moment at the world’s most serious party. At Los Angeles’s A&M Recording Studios, a highly pedigreed group of singing multimillionaires have come together with one goal: to help Africa’s starving. Their recording, “We Are the World,” fresh from the pens of Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie, came out two weeks ago and is getting unprecedented air play. That January night three visitors from LIFE were the only outsiders on hand.

AN ANTHEM FOR A NEW AGE OF GIVING

This is the inside story of a hit song and how it is raising millions for famine relief in Ethiopia and the rest of Africa. Free-lance journalist David Breskin and LIFE writer Cheryl McCall were on the scene in Los Angeles for more than a week before the recording session—itself a unique, night-long happening that is described here too.

January 22: Security is tight outside Kenny Rogers’s Lion Share Recording Studio on Beverly Boulevard. Inside, there is a commotion in Studio A: Skeet, Smelly, Stevie and Q are carrying on. “Skeet” is a relic of Lionel Richie’s childhood. When friends called Michael Jackson Funky, he said it was a dirty word. They made it “Smelly.” With Stevie Wonder and producer Quincy “Q” Jones, they are running through what they call an Acapulco (a cappella) version of the song Michael and Lionel have just written—but not yet polished. Tonight the basic instrumental track will be recorded. Lionel and Michael will add a “guide” vocal, and 50 cassettes of the song will be duped for the invited performers. In addition to the four stars, the studio is swimming in musicians, techies, video crews, retinues, assistants, organizers and spilled popcorn from a fierce shoot-out between Michael and his constant companion, Emmanuel Lewis, 14, star of Webster.

The studio is a blond-wood, track-lit affair, all California plush and casual, and the mood in the room reflects it: Everyone is relaxed and upbeat. During an instrumental run-through. Michael, Lionel and friends huddle over a copy of the National Enquirer, whose cover story is on Joanna Carson. Her claim that she can’t live on $44,600 a month becomes an absurd motif for the evening.

After the fifth take, the studio musicians listen to the playback in the control room. Quincy tells them he wants one more, “because you won’t be thinking about it this time. I still hear a little bit of thought in there now.” During the sixth take, Lionel kneels by the mixing board to listen; Michael sits on the couch with his head nodding to the beat and his lap full of Emmanuel. Finally Q gets what he wants.

To compose the song, Michael and Lionel had hung out for four evenings, visiting in each other’s homes. No notes were written. Then after spending a day apart, Lionel gave Michael two melodic ideas on a tape. Michael said, “I got it. Thanks.” With those lines as a beginning, Michael sneaked into the studio that night. “I went ahead without even Lionel knowing,” he says. “I couldn’t wait. I went in and came out the same night with all the music completed. I presented the demo to Quincy and Lionel, and they were in shock—they didn’t expect to see something this quick. They loved it.” Lionel says, “Two nights later we got together and nailed all the lyrics in two and a half hours. No playing around. Straight to it.” There was one weekend to spare before the recording session.

In the studio Michael and Lionel begin laying down the vocal. Between takes, Michael drums his fingers against the baffles in rhythmic bursts. They embellish the melody, improvising wildly. Quincy reminds them that the purpose of this vocal is simply to teach the others the song. “Play it straight,” he advises.

The major problem of the evening is the lyrics, specifically the third line of the chorus: “There’s a chance we’re taking, we’re taking our own lives.” Quincy tells them he’s worried the second part of the line will be considered a reference to suicide. Michael says, “I thought about that too.” They listen to a playback of the chorus. and Lionel immediately offers a change: “We’re saving our own lives.” Quincy suggests the first phrase be changed as well. “One thing we don’t want to do, especially with this group, is look like we’re patting ourselves on the back. So it’s really, ‘There’s a choice we’re making.’” Michael sings the new line. Lionel responds, “You’re right. I love it.” After a little post-midnight revising, the lyrics are set.

They finish a chorus of pure melodic sounds, “sha-lum sha-lingay,” at about 1:30 a.m., at which point Q calls from the control room, “If we get it too good, someone’s gonna start playing it on the radio. Let’s not put anything more on this tape.”

January 24: The cassette dupe of “We Are the World” goes out to all the artists via Federal Express, which, in the spirit of the event, foots the bill. Enclosed is a letter from Q addressed to My Fellow Artists. Part of it has a Mission Impossible feel to it: “The cassettes are numbered, and I can’t express how important it is not to let this material out of your hands. Please do not make copies, and return this cassette the night of the 28th. . . .” He closes, “In the years to come, when your children ask, ‘What did mommy and daddy do for the war against world famine?’ you can say proudly this was your contribution.”

January 25: Ken Kragen, manager of Richie and Rogers and organizer of this songfest, chairs a production meeting in a stucco bungalow just off Sunset Boulevard. Present are some 20 associates—variously involved in legal matters; flower and plant procurement; talent coordination; promotion; transportation; interviewing; art direction; food, drink and ice acquisition; video documentation; public relations; traffic control; credentials; security and leaks. Kragen addresses the last problem immediately: “The single most damaging piece of information is where we’re doing this. If that shows up anywhere, we’ve got a chaotic situation that could totally destroy the project. The moment a Prince, a Michael Jackson, a Bob Dylan—I guarantee you!—drives up and sees a mob around that studio, he will never come in.”

Over at Lion Share Studio, Tom Bahler, Q’s associate producer and vocal arranger, shows up looking like a man who has the world on his shoulders but is happy about it. He retreats to a back room, where he begins to think about solos. He says of the powerful talent at his disposal. “It’s like vocal arranging in a perfect world.” Q sees the other side of the equation: “It’s like putting a watermelon in a Coke bottle.” The goal is to match each solo line with the right voice.

January 26: At the “choreography” session in Richie’s house, decisions are made as to where each artist will stand. Let’s see, Willie goes over here, and Bruce over there, Diana like so and. . . .

January 28: This is the big night. “God is with us,” cries Quincy Jones, on being told Michael Jackson has pulled into the heavily guarded parking lot on time, 9:00 p.m. Michael has come earlier than the others to record a vocal chorus by himself. He horses around with Q, then touches up his rouged cheeks. He walks into the studio and begins singing, sunglassed and solitary, thumbs in his front pockets.

Steve Perry, lead singer of Journey, hurries into the control room, peers through the window at Michael. He asks, “Am I dreaming? Am I on drugs or what?” One by one, the stars show up. When Ray Charles arrives, Billy Joel says, “That’s like the Statue of Liberty walking in.” Quincy introduces them, “Ray, this is the guy who wrote ‘New York State of Mind.’ “Joel is trembling.

Bob Dylan slouches in, stone-faced, and sits down in the seat closest to the door. Bruce Springsteen arrives with no entourage, no bodyguards. He simply parked his rented car across the street from the studio, breezed by security and entered the control room, where he’s smothered in giggles and hugs by the Pointer Sisters. He hugs Dylan. He hugs Joel. They all watch Michael. After a take, Quincy calls out, “Sounds great, Smelly!”

At this point, Diana Ross makes a grand entrance, screaming, “I love this song!” From a dramatic, dipping hug with Quincy (the man is a hugging machine), Diana jumps onto “Bobby” Dylan’s lap for a few minutes and then asks Dionne Warwick about her perfume, “Boy, you smell so good, what is that?”

Kenny Rogers comes through the door. Stevie Wonder is led in. Paul Simon sneaks in and asks, “Is there somewhere I can put my coat?” In a few minutes the control room is in the throes of perhaps the world’s first documented case of starlock: no one can move in any direction. It’s hot and happy and chaotic, a din of famous voices, but no work is getting done. Quincy yells, “Let’s move this into the studio, please.”

10:30 p.m.: Each performer’s name is on a piece of silver gaffer’s tape on the risers. Everyone wanders around looking for his or her spot. When Lionel Richie rushes in, having just hosted the American Music Awards and won six himself, he tells Bette Midler how fine she looks.

Bob Geldof is introduced to applause. He steps onto Quincy’s podium to address the group, with fire in his voice: “I think what’s happening in Africa is a crime of historic proportions. . . .” He goes on to detail his experience in Ethiopia: “You walk into one of the corrugated iron huts and you see meningitis and malaria and typhoid buzzing about the air. And you see dead bodies lying side by side with the live ones. In some of the camps you see 15 bags of flour for 27,500 people. And I assume that’s why we’re all here tonight.”

Ken Kragen explains how the money will be spent—40 percent for immediate relief, 40 percent for slightly longer-term relief, the rest for long-term, self-reliant development, and perhaps some funds for the hungry and homeless of America. All the performers and technicians have donated their services; a caterer, the food.

Q runs through the agenda. As Michael’s voice singing the guide chorus fills the headphones, Quincy shouts, “O.K., let’s start chopping wood.” They begin to sing. “Take it to church,” he calls.

Midnight: After several takes, a break is called. Billy Joel hustles over to the guests’ party in the adjoining soundstage (where they’re watching the recording via video hookup) and locates fiancée Christie Brinkley in the crowd of 500 that includes Jane Fonda, Brooke Shields, Steve Martin and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Joel squeezes her into the studio, introducing her to Dylan and Paul Simon. Christie looks starstruck. By the time she leaves the room, she’s talking about mobilizing the fashion industry for a similar effort.

Ray Charles sits at the piano for a spell, straddling the bench, and talks of his visits to Africa: “I’ve put my hands on these children, and their skin feels like cellophane on bone. You have to feel that, man. That’s unreal stuff.”

1:00 a.m.: As the chorus reconvenes, Stevie Wonder announces that he would like to substitute a line in Swahili for the “sha-lum sha-lingay” sound. Waylon Jennings, figuring no good ole boy ever sang in Swahili, leaves the studio, never to return. Before long a full-fledged creative conflict breaks out. The video feed to the soundstage party is abruptly cut, so that the guests will be spared an all-star argument, which follows: Geldof points out that Ethiopians do not speak Swahili, and Lauper adds that it’s like “singing to the English in German.” Michael Jackson votes to keep “sha-lum sha-lingay,” but after this is sung a few times it too runs into opposition. Quietly a coalition forms among Lauper, Al Jarreau and Paul Simon—who want to find something meaningful to sing in English.

“We can make a meaning,” cries Jarreau, and soon he produces a new line: “One world, Our world.” Lauper exudes, “That’s right! Ain’t what we’re doing trying to unite the world?” Q asks the group, “Can everyone agree on ‘One World’?” Stevie is bummed. Tina Turner, eyes closed from fatigue, says to no one, “I like sha-lum better—who cares what it means?” But most acquiesce. It does get changed one more time, to “One World, Our Children.” They begin rehearsing the new part. It sounds beautiful, fitting. The video connection is restored to the bewildered guests. Then in a sudden tribute to Harry Belafonte, who had first suggested this benefit recording session, Stevie begins singing “The Banana Boat Song” and everyone joins in with “Day-O!”

3:00 a.m.: A photograph is taken for the album cover and poster, and it’s time for the solos. Lionel and Quincy call the performers over to the piano. There will be short duets between the solos. Stevie will harmonize with Lionel, Kenny Rogers with Paul Simon, Tina with Billy Joel, Willie with Dionne, and so on. Since Prince did not show up, his line is given to Huey Lewis. Cyndi Lauper pulls Q away from the group and shyly asks him, “Is it all right If I improvise?” Quincy sounds thrilled. “Absolutely. This is not the Rite of Spring.”

4:00 a.m.: The soloists stand in a semicircle. Their mood is light-hearted. Just as they are ready to sing, two Ethiopian women, guests of Stevie Wonder, come into the room. One woman says, tearily, “Thank you on behalf of everyone from our country.” The performers are stunned. No one speaks: a deep, penetrating silence. The women cry; eventually, so do the performers. The shaken visitors are led from the room. Quincy breaks the silence, saying softly, “It’s time to sing.”

5:15 a.m.: The soloists finish a second complete pass around the room, a splendid take, a keeper. Immediately, Quincy is asking, “Where’s Bobby Dylan? Let’s get Bobby in here.”

5:30 a.m.: Stevie rehearses Dylan at the piano for a solo version of the chorus. Dylan is tentative. Stevie is doing a better “Dylan” than Dylan—more whining exaggeration—and explains, “Do it more like this.” After 20 minutes of coaching from Wonder, Dylan approaches the microphone. He barely manages a mumble. Lionel clears almost everyone out. With each successive take, Dylan gets stronger—more like himself. He asks Stevie to play the piano behind him. Q rushes in after the take, “That’s it, that’s it, that’s the statement.” Dylan, unconvinced, mutters, “That wasn’t any good.” Lionel tells him, “Trust me.” As Q gives him a bear hug and whispers, “It’s great,” Dylan finally smiles. “Well, if you say so.”

Soon after, Jarreau corners Dylan by the piano. He’s choked up. “Bobby,” Jarreau says, holding back tears, “in my own stupid way I just want to tell you I love you.” Dylan slinks away without even looking at him. Jarreau walks to the door of the studio, looks back at Dylan, cries, “My idol,” bursts into tears and leaves.

Enter Bruce Springsteen for his solo chorus. “You sounded fantastic, Dylan.” he calls to Bob as he steps to the mike. Dylan leans against the wall to watch Bruce work. Bruce asks Q for some direction. Q: “It’s like being a cheerleader of the chorus.” Bruce: “I’ll give it a shot.” Springsteen sticks his sheet music in his back jeans pocket. His voice is rough, pained, reduced to essence—perfect for this part. (He had done a four-hour show in Syracuse the night before and had flown all day to get here.) After a nearly flawless first take, he humbly asks Q, “Something like that?” Q can only laugh. “Exactly like that.”

Bette Midler hugs Dylan, tells him, “Good night, dearest.” Springsteen listens to a playback on the studio monitors, approves, gives Lionel his autograph and walks out of the studio, past six waiting limos in the parking lot, across the street to his rent-a-car and is gone. By 8:00 a.m. the rest have disappeared into the morning too.

7:30 p.m.: Lionel Richie’s house. Lionel has been sleeping since 10:00 a.m. The phone rings. It’s Steve Perry, calling from his L.A. hotel room. Perry says he just had to call somebody. Lionel asks him what’s wrong. Perry says that he slept well. He got up and ordered room service. They brought him breakfast. He sat down. He pulled the silver cover off the food. And then he started crying.