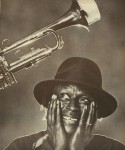

Miles Davis

Searching for Miles: Theme and variations on the life of a trumpeter

Searching for Miles: Theme and variations on the life of a trumpeterRolling Stone

September 29, 1983

Dear Sir:

I started Miles Davis out on trumpet in the sixth grade at the Crispus Attucks School about September 1937. He continued training with me at Lincoln Junior High School in 1938. He was playing good then. He remained with me through senior high school. He was one of my most progressive students in the Lincoln High School Band (and the instrumental program in Public School District 189 in East St. Louis, Illinois).

Miles Dewey Davis III was born on May 25th, 1926, in Alton, Illinois. Miles’ father was not only a respected citizen and dentist but a prosperous landowner. As the result of Miles’ outstanding ability, I got his father to get him a trumpet of his own. After great success in the Lincoln High School Concert and Marching Band, he graduated about 1943. He was one of the best musicians I ever taught in instrumental music. He received all first awards with my band groups that competed in the Illinois State High School Music Association contests.

I had him try out with Eddie Randle’s St. Louis “Blue Devils” Jazz Band. Miles gained recognition and received a scholarship to the Juilliard School of Music. His mother wanted him to go to Fisk University, in Nashville, Tennessee. It took Miles almost a year to convince his father to allow him to go to New York, but he finally relented, much to the dismay of his mother, Mrs. Davis. When Miles was nineteen, still naive but strong-willed, he arrived in New York City.

Miles had mixed feelings about Juilliard. He really had gone to New York to try to hook up with Charlie Parker and his band. He met Charlie Parker in St. Louis at the Riveria Nite Club on Delmar at Taylor Avenue. (Big bands played there — Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstine, Jimmy Lunceford, Count Basie and others.) I think one semester was enough for Miles at Juilliard. He caught up with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. After a while in New York, Miles lived with Parker one year. On Parker’s first record as a leader, he decided to take Miles. From then until present, Miles Dewey Davis III has been one of the top jazz musicians.

Sincerely,

Elwood C. Buchanon Sr.

P.S. Send me about six copies of the article or magazine.

“I drive my yellow one in New York. Police don’t bother me ’cause it looks like a cab. Wsssshhhhtt! They figure, Oh shit, that’s just a taxi. I did that shit once in front of a brother, I did one of those funny things that only a Ferrari can do. He stopped me and said, ‘Goddamn Miles, why you do that shit?’ I said, ‘What would you do if you had this motherfucker?’ And he said, ‘Okay, go ahead.’ The shit was outrageous, though. Only a Ferrari would do that shit. I love a Ferrari, man. The white cops, they all know me by now. Motherfuckers say, ‘Oh, that’s just him.’”

■

Laughter cracks the scorched whisper of his voice. He slouches over a sketch pad on his Houston hotel-suite bed, drawing a woman with slashing jaw, electrocuted hair, ballerina legs. Damn, this bitch is fine. His teeth battle with a wad of gum, and his eyes swing up from the fine bitch to college hoops on the tube and then back again. Anticipating a rubdown from his trainer and gofer, Zeke, he wears only a jockstrap and open robe. Sweat rolls down the balding head he doesn’t let his audiences see (his splendid haberdashery), and he rasps, with irritation and amusement, “Better ask me some questions, ‘cause your time is runnin’ out fasssst.”

Though Miles rarely cooperates with the press, for some reason known only to himself, he’s consented to an interview. Over the next weeks, there are several. I travel with his band in Texas, and they talk, mostly off-the-record. I speak with sister, brother, daughter, nephew, teachers, students, producers, managers, collaborators. Yellowed clips of exploits, both with and without horn, crinkle back to the Forties, and I’m buried, searching for the key. After Miles wins his latest Grammy, he calls me from the Ritz-Carlton in Chicago. When I answer the phone, he whines, “You again?” and hangs up. Calls right back, and charmingly asks what more I’d like to know. That’s just him. We all know him by now.

■

“White people do that, man. They say, ‘he does this and he don’t do that, and he fucks five girls a night and he makes $10,000 a second, but he’s a nice guy and his mother threw him out when he was two.’ Fuck that! Why do they ask all those rock stars that shit? ‘She wears her hair like this and he has fifty dozen girls, her life is an open book, but she’s misunderstood.’ Who they fuck and why they fuck and this song has a message. White people do that shit. What does it mean? I don’t like that. It’s all just music.”

■

Miles Davis is arguably the most important of all living American musicians. His music stands with the greatest of the century. It begins with him spitting rice and beans to build up his lip as he walks to school. His mother wants him to play violin, his father overrules with the trumpet. Mother wants him to be a dentist like father, father wants him to be the best at whatever he chooses. Father wins that argument. If you’re a thief, don’t be no jive thief.

In between school, a paper route, work in dad’s lab and weekend jam sessions paying three dollars a night, young Miles hangs out at his father’s farm. “Not a bullshit farm, a gentleman’s farm,” says brother Vernon. “Two hundred acres with a lake and one of those Southern colonial homes and a Jaguar in the driveway.” Miles fishes, hunts, rides one of thirteen horses. At sixteen, Miles marries Irene — the first of four wives. Baby Cheryl is already on the way. Picking cotton does not teach anyone how to play the blues.

■

“If I was black for sixteen years and I turned white — I mean my insides and everything — shit, I’d commit suicide. ’Cause whites have knowledge but no rhythm. Classical music was invented ’cause white people didn’t have no rhythm, and they could write it and plan it and all. Once you have a taste of rhythm — say, for sixteen years — and someone say, ‘Do you want to be white, with all the trimmings?’ Shit no. Brooks Brothers suit is all right, but I’m talking about the feeling.

“Now, did you see last night, I was playing a blues and I go over and bend down and play to that fat woman in the second row. She says, ‘That’s right, Miles, come on over here, you can stay over here.’ So then I play something real fast, and she says, ‘Not like that, though. Go back over there if you’re gonna play that shit.’ Now, do you think a white person would tell me that? They don’t even know what she’s talking about. She’s talking about the bluuueeesss. In my hometown, if you don’t play the blues, shit, them motherfuckers go to ordering drinks, but if you play the blues, they’ll stay right there. That fat bitch, she’d have me blowing all night.”

■

All night, 1945, swinging on fifty-second Street, blowing his allowance and horn, Miles slips into the ferocious lives of Charlie “Bird” Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and up onto the bandstand of the be-bop revolution. His tone is pure, round, without vibrato. On his first recordings with Bird, he shows technical limitations but also the first signs of lyrical brilliance. He can’t play as high or as fast as Dizzy; he sticks to the middle registers. He makes less mean more. Bird and Miles have a stormy love-hate relationship, and Bird humiliates him with games on the bandstand. Makes you feel one foot tall. They split in ’48.

Be-bop is only the first of many movements Miles will either captain or observe from the crow’s nest. Soon he’s in arranger Gil Evans’ one-room basement apartment behind a Chinese laundry, working on a way to calm the frenetic and scalding turbulence of be-bop without chilling the passion. It’s called “cool jazz,” and until Evans orchestrates it and Miles plays it, the trumpet is but half a horn; then it’s capable of introspection, light and shadows, restraint, repose. Miles quickly develops an economy of expression unmatched in American improvisation.

He travels to Paris, where the French lionize him. He hangs out with Jean-Paul Sartre on the Left Bank. Miles doesn’t understand Sartre, but Sartre knows existentialist trumpet when he hears it. When Miles comes back to the States, he finds heroin and checks out for four years. He lies, steals, cheats, pimps, his trumpet turns to metal.

■

“Max Roach walked up to me one day on the street, we were real tight, and said, ‘Damn, man, you sure do look good, what’s happening?’ But I could tell he was looking at me. And as he left, he touched me in my pocket, put a hundred dollars in my pocket. And I didn’t dig it until he left — telling me I looked good and then giving me a hundred dollars like I’m a fucking bum. And that’s all you are when you use that shit. I went right to St. Louis and kicked.”

■

Cold turkey on the farm, followed by a triumphant return at the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival. This time it’s called “hard bop,” and it reenergizes the blues with elegant modernity and streamlined muscle. For the next twenty years, Miles doesn’t play music so much as invent it. With the help of those in his employ — always the best and the brightest — his career becomes a rich quarrel between tradition and innovation. He collaborates with Gil Evans on a stunning series of orchestral recordings — Sketches of Spain, Porgy and Bess, Miles Ahead — that blend classical, ethnic and Afro-American idioms. He gives ballads and standards a new emotional depth through his use of the harmon mute. He junks chord changes and soars off with John Coltrane on modal excursions. He writes and plays with increasing abstraction and freedom while leading (and following) a band of Young Turks — Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock. Finally, he sums up the electric spirit of the late Sixties and early Seventies by supervising the birth and development of jazz-rock fusion. Restless, relentless, he synergizes new vocabularies, masters the language, then moves on with another generation in tow. He’s the Picasso of the invisible art.

By September 1975, in New York’s Central Park, he’s playing an excoriating version of heavy metal funk ‘n’ roll — full of dark distortion, demonic intensity, tortured guitars, screeching trumpet. Then he stops. Pulls away, retires to a dark space on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Leaves behind over fifty albums, no clues.

I loved it when he used to dress so cute in those suits. When I was a teenager. Those Italian suits. Polka-dot ties. Those cute suits. Oh, he was so cute. I used to love it when he put on those cute suits.

— Cheryl Davis

I call him King Tut because King Tut was a black king in his time and Miles is the black prince from this time. So I call him King Tut. I couldn’t call him Prince Charles, could I?

— Vernon Davis

■

Miles Davis has an image. Nasty and notorious, arrogant and whimsical, he does nothing he doesn’t want to do, and he makes a point of it. When he feels like biting his producer’s ear, he bites. That’s a nice WHITE ear. When he decides he doesn’t want to speak to this same producer for three years, he doesn’t. When the producer, Teo Macero, calls every so often, Miles shouts, “So what?” and hangs up. Irascible and insolent, he’s the Evil Genius, the Sorcerer, the Prince of Darkness. He won’t bow to his audience for the same reason doctors don’t bow to their patients, won’t face his audience for the same reason conductors don’t face theirs. He doesn’t speak to his audience because he plays the trumpet for a living.

Miles is only five foot four, but he can look down on whomever he sees. His attitude is in his heels: boxer’s stance, his high-profile mystery and intrigue, his proud pose as the anti-Tom. He may arrive late, walk offstage after his solos, sneer superciliously from behind his shades. Despite some superficial complaints, all this secretly delights his audience. They wouldn’t want him any other way.

Miles Davis is aware of his image and knows how to use it. He knows there are women in Sweden in love with his photograph and young men in Japan wearing his glasses and babies in Nigeria with his name. Whether it be with polka-dot tie, dashiki or Japanese jump suit, gangster cool or green trumpet, his ascent to the peak of Bad Motherfuckerdom ensures his currency even among people who don’t make a steady diet of jazz. It’s not just the music that puts him — and who else among instrumentalists? — on the society and gossip pages. It’s his magnetism, his sexuality, his hubris.

And his talent for trouble: cops arrest him for narcotics and brass knuckles and .25-caliber automatics, beat him over the head outside Birdland. Racketeers shoot through the door of his Ferrari, and he breaks both legs smashing up his Lambourghini. A woman sues him for unlawful imprisonment and menacing in his apartment, a man for being thrown down the stairs. Miles Davis is a pop star.

But while most pop stars’ music only confirms and bolsters their public images, Miles’ art always strips bare the pretense of his facade. Behind the veil of his rancorous public profile, the music reveals the person: romantic, lonely, vulnerable, full of pain and pathos and humor and joy, all the recombinant powers of the heart. Even the world’s largest corporation recognizes his potent emotional pull when, in the late Fifties, it runs a magazine ad showing a man talking to a woman on the phone (their product), saying, “I was listening to Miles playing ‘My Funny Valentine,’ and I started thinking about you.” Miles Davis is a funny valentine.

■

“If I didn’t play trumpet, I don’t know what I would have done. I couldn’t stay in an office. I’d do some kind of research. That W-H-Y is always my first word, you know. I’d do research, ’cause I like to see why things are, how they are, the shape and flesh and everything. I’m one of them motherfuckers. I’ll never have an easy life. I’ll always be in trouble because my nature is to say ‘why?’ to things I don’t know anything about. And get in ’em, and find out myself.”

For six years, Miles researches pain and pleasure at his Upper West Side townhouse. He doesn’t play trumpet, doesn’t perform or record. There is no music in his head, and it’s killing him, if his illnesses aren’t already: arthritis, bursitis, stomach ulcers, throat polyps, pneumonia, infections, repeated operations on a disintegrated hip. The doctors move around the bones in his body. Miles moves around the pain with booze, barbiturates and cocaine.

He cooks his famous bouillabaisse. He doesn’t sleep. He calls his sister in Chicago to ask her what time it is. It’s an excuse for contact. He goes to after-hours joints and provokes bar fights, throwing tantrums and ashtrays. He gets carried out, piggyback, by one of his right-hand men. Always, he’s with one of his revolving platoon of right-hand men. He can’t stand to be alone. He lives on the telephone and with the television on. His apartment looks bombed out.

Many times he’d say, “Go to Leo’s Liquor Store and get jugs of Mateus wine.” And I’d go hang out with him at some girl’s place. He’d say, “Here’s your bottle of wine and your stash of coke,” and then he’d go into the bedroom with his bottle of wine and his coke, and we’d sit there and wait for him to finish up whatever he was up to. It was weird. Calls at 5:30 in the morning, he says, “Get up here and keep me from killing Loretta.” That was one of his girlfriends.

I’d get up there, and Loretta and him would be going at each other with these huge scissors that you could just put through somebody. I’d have to break the fight up and hide the scissors, and he’d punch her out and I’d cool him out and he’d cool the police out to keep from being arrrested.

—a right-hand man

■

Miles chases a man out of his townhouse. The man runs through his backyard and climbs over a wall. Miles tries to follow him over the wall but loses his grip. To break his fall, he puts out his hands, but his wrists are brittle with bursitis. He’s in agony, stretched out on his stomach, screaming. A woman from a neighboring building leans out her window and shouts, “What’s going on out here?” Miles shoots back, “I’m fucking your mother.” Through all his pain, humor is his only home.

The backyard is about as far as Miles will go. He almost never leaves the apartment. He brags about being the best at whatever he chooses, and now he proves best at doing nothing. He’s bored. He’s rich. Under a special deal, CBS sends him an allowance whether he records or not. (Only he and Vladimir Horowitz have this arrangement.) A local pharmacy sends him drugs without a doctor’s prescription. The press dubs him “the Howard Hughes of Jazz.”

He stands on his sunken porch, drooling from a Heineken bottle, and introduces himself to a female passerby with a squeeze of her tit. Mick Jagger comes by to genuflect. It’s been arranged. Miles keeps him waiting in his limo for hours and then decides he doesn’t want to meet him. Sends the little limey away. He shoots happiness into his leg with a dirty needle and pays no mind until one day he can’t walk. The infection is severe; Miles faces amputation. Another huge scar, and it’s saved. CBS tries to interest him in recording projects, but his mind is divorced from his fingers. Doctors ask him if he wants to live. Friends expect a funeral.

When Miles plays, it takes a tremendous amount of aggression, because everything he plays is so hard. Well, if he doesn’t use that aggression on the horn, he gets it out with people. Chasing people, fighting, with guns, all sorts of things were happening up there: kicking people down the stairs, falling down the stairs himself. One time he was wrestling with one of his kids and broke his leg. He had to find an outlet for some of those emotions he uses in his work. And I wouldn’t say Miles never turned his anger against himself. He’s dabbled in everything not good for you. And I think some of his illnesses were his way of turning against himself, his masochism.

—Gil Evans

■

“I was just having myself a good time. But I don’t like to lay back. I don’t like to relax. Show me a motherfucker that’s relaxed, and I’ll show you a motherfucker that’s afraid of success. When I was out, when I didn’t work, Dizzy came by and said, ‘Man get the fuck in trumpet and play it, motherfucker.’ I said, ‘Man, if you don’t get out of my house, I’ll break your fucking neck.’ He said, ‘No you won’t.’ He’s a funny motherfucker, boy. Dizzy say, ‘Man, you’re supposed to play music.’ I said I didn’t feel like it. But you know, he was right.”

■

Finally, Miles feels like it. Though still phlegmatic and drunk, he’s at long last bored with boredom. He’s also not as wealthy as he once was. CBS has cut off his steady stream of advances in an effort to cut potential losses (if he never records again) and lure him back into the studio. Miles is still comfortable, but he needs to be more than comfy, and he’ll have to work some to keep himself in limo trunkloads of new Italian shoes. Besides, this will be a challenge for a man who thrives on proving things—mostly to himself.

To assist him, he recruits a young, unknown, white, straight-arrow saxophonist named Bill Evans. Evans visits Miles every day during one of his hospital gigs, protects him during his late-night perambulations, runs his errands. Miles calls him at all hours, and Evans helps him form a new band. They have a sick father /healthy son relationship. Evans idolizes Miles, gives him energy and ideas, and Miles gives him his first gig out of college. He feels like it.

In the summer of 1981, at the Kix nightclub in Boston, Miles Davis makes his comeback appearance. He uses a battery-pack microphone on his trumpet, which gives him all the mobility his shaky legs will allow. He moves to the front of the stage for his solos, bends his legs into a squat and hunches over the horn until the bell is inches from the ground. It’s a protected, fetuslike position. Spotting a kid in a wheelchair, he limps into the audience. The kid has no legs. Miles leans over the paraplegic, puts the trumpet right up to his torso and plays a long, beautiful solo.

■

Cicely Tyson and Miles Davis are skinny and gorgeous after going vegetarian for eight days at the upstate Pawling Health Manor. Their limo carted home cases of kiwi and papaya, bushels of corn and apples, sacks of cukes, carrots, broccoli, pineapples, a tub of home-grown lettuce and an encyclopedia of carrot-cutlet recipes.

–New York Post, November 4th, 1982

Cicely Tyson and Miles Davis have a love affair from 1966 to 1969. She wants to marry him, and he puts her on the cover of an album, Sorcerer. After they split, she calls him each New Year’s Eve. He is not having particularly happy new years. She tells him to play his trumpet. He hangs up on her. She calls right back. Cicely Tyson will not take no for an answer. She calls all his bluffs, defuses all his games; she knows the hurting, shy little boy behind his gruff facade. One night she calls, and for the first time in years, he plays to her over the phone. As he falls back in love with the horn, he falls back in love with Cicely. In a midnight ceremony on Thanksgiving Day 1981, at best man Bill Cosby’s Massachusetts estate, the honorable Andrew Young, mayor of Atlanta and former ambassador to the United Nations, marries Cicely Tyson and Miles Davis.

■

“Cicely was in Africa, I was in New York. Shit, I woke up one morning, I couldn’t even move my fingers. It stayed like that for a month. I go to the doctor and he says I got the Honeymoon Paralysis. Honeymoon Paralysis, that’s when guys get so tired from fucking so much that they go to sleep on their hand and it wakes up numb. It was a stroke. And he told Cicely that I would never use this hand again, this one I’m drawing with here.”

■

After his stroke and her return, Cicely takes Miles to her Chinese doctor for acupuncture. He responds well to treatment. He quits smoking, drinking, snorting, pill popping, replacing those habits with new daily dependencies: Chinese herbs, mineral water, swimming, sketching, working out. (His doctor also tells him to cut down on fucking, but Miles has his limits.) Cicely takes Miles out to benefits, dinners, balls. Cicely goes on tour with Miles, lugging her food processor from hotel suite to hotel suite, carrying it on the plane from gig to gig. Cicely Tyson is giving Miles Davis a personality lift.

When heavy rains threaten to dislodge Southern California from the mainland, Cicely leaves the tour to attend to their Malibu house — one of five shared residences. This upsets Miles, breaks his rhythm. But Cicely will be in his hotel room shortly. A Houston TV station is showing her portrayal of Harriet Tubman in A Woman Called Moses. Miles tells his guest to turn on the set. He’s speaking on the phone to his veteran drummer, Al Foster, who’s staying across town at the Holiday Inn. Miles stays in a different—better—hotel than the rest of the band. “Just turn the channel till you see black people….No, man, not the basketball game…there.” A few minutes of Grandma Moses and he orders, “Man, I don’t want to see that shit, turn that off. Fuck that, man, Zeke told me they’re gonna hook her up to a wagon and all that shit. I can’t watch that, hitching her up to a wagon. Make me mad. I’ll go off, laying here by myself. Make me break some glasses.” The guest says it’s nice she’s on TV, wagon or no. “Yeah,” croaks Miles, “it means I’m gonna get a raise.”

■

Miles Saunters onstage in Texas in a black fedora, sunglasses, black shirt, a red leather fringed jacket, black pants and bright red high-heeled boots. He fiddles with his synthesizer, which he’s taken to playing concurrently with the trumpet — one with each hand. He does this because “synthesizers are programmed to sound white—that’s how prejudiced white people are — so if I don’t play over it, it will sound mechanical.” Onstage, among Miles’ six musicians, are three whites: Bill Evans and guitarists Mike Stern and John Scofield. Among his loves are Sinatra and Stockhausen. Miles Davis is no racist.

The music he now plays is conservative. In the absence of a new conceptual statement, Miles curates his career during each performance, presenting a collage of uptempo funk, oddly strolling blues and singsong ballads haunted with Spanish and bop motifs. His trumpet playing is extravagant, by turns dramatic and desultory. He is healthy enough now to play anything he wants on the horn, but seems unsure where to take the music as a whole — and so he toys with it.

He walks forward and backward across the front of the stage. He stops to stick out his tongue, show a lady his wedding band, count the photographers, with whom he plays cat-and-mouse. He attempts to empty his spit valve on one, puts the bell of the horn over the camera of another. Laughter from the audience. Night after night, in the middle of a solo, he hitches up his pants to expose his fire-engine-red boots. Much applause. Then he engages saxist Evans in a humiliating little game of call-and-response, in which Evans inevitably fails to mimic exactly the master’s lines. Shouts of “School him, Miles” and “That’s not what he told you” come from the crowd. Miles then directs Evans over to the electric piano — sometimes by the elbow—as if to suggest a new instrument. When he tires of Evans’ piano solo, he points him back to the saxophone. It’s a denigrating display of a “good-natured joke,” and it makes Evans feel about one foot tall.

This transformation of Miles from a forbiddingly serious artist to a showbiz ham is an unexpected joy for some concertgoers, a depressing experience for others. As for the band, they’re in a different hotel even on the same stage. No matter. Miles is having fun cashing in on his comeback. He commands top dollar in the States, an eighty-dollar ticket in Paris and receives nearly $100,000 a night in Japan.

He also now insists, “I don’t like to record at all, live or studio. I just do it to make money.” He releases three postcomeback records that seem to prove his point: 1981’s tepid warmup The Man with the Horn, ’82’s live hit-and-miss We Want Miles and the new Star People, with its wandering blues and fragmented funk. Still, he wins a Grammy for We Want Miles, though he insists he doesn’t know why. He wins it for that red leather fringed jacket.

When he goes to Los Angeles to perform on the show, he stays at Beverly Hills’ sumptuous L’Ermitage Hotel. While there, he orders his white Ferrari airlifted from New York to L. A., towed from the airport and parked in front of the hotel. The Ferrari can’t be driven — it’s had a mechanical problem for some time—but it’s a stage prop that makes him feel good. Miles Davis feels good these days.

■

Miles Davis comes off the plane last in Austin, Texas. An airport employee waits to drive him to his limo in an electric cart. It’s too long a walk to the terminal. Miles eases up onto his seat. Shrouded by his fedora and shades, he listens to last night’s concert on his Walkman. He wears his headphones upside down, under his chin, and presses them to his ears to block out the spastic beeping of the cart, warning all that King Tut is coming. Travelers headed for their gates part to let him pass. They all stare. Those that know nudge each other, and a middle-aged woman drawls, “It’s that Davis man.” A few heads tilt under cowboy hats, like dogs’ heads do when they’re puzzled, as if to ask: who could this man possibly be?