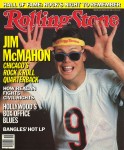

Jim McMahon

BORN TO BE WILD

BORN TO BE WILDRolling Stone

March 13, 1986

Chicago Bears quarterback Jim McMahon may be football’s bad boy, but he sure knows how to shake, rattle and roll out.

So you walk into 4141, this yuppie club in uptown New Orleans on the Thursday night before Super Sunday, and this blonde in a chocolate cashmere sweater-and-slacks combo comes up and says: “Let me tell you something, Jim. I am a middle-aged woman, and I have big tits, and you know what that means!” Right, it means you have to escape with your pals, and quick, to a corner table tucked behind the dance floor.

You take a pull on your Moosehead and burp a little memory of dinner: it was ’taters and steak and onion rings and beer. You were on your best behavior at the best steakhouse in New Orleans. Still, there were moments for comedy. One preppie, a Choate man, approached you: “I have a problem: my girlfriend is pissed at me, so can you make this out to her and say maybe, ‘He’s a good guy’?” You signed, “Get rid of him, Jim McMahon #9.” A woman in search of signature made a suggestive remark that sent you rough-housing with Kurt Becker, offensive lineman and roommate, who was seated next to you. The woman apologized: “Oh, did I start something between you two?” You answered politely: “No, ma’am. Just ’cause I rub his penis doesn’t mean we’re friends.” When the table talk turned to reincarnation, you announced your desire to “come back as a woman’s bicycle seat.” And when the National Football League’s chief drug enforcer strolled into the joint for supper, you promised to host the first Hazelden Open Golf Tournament — named in honor of the famous drug-rehab clinic — featuring mixed drinks at every hole. But on the whole, dinner was quiet and uneventful. Things were sure to pick up.

A young lady is attempting to do just that. She has you cornered at the corner table and is falling into your lap in a Southern-belle swoon. She wears a button that asks, are we having fun yet? “Not really,” you think, and duck out with your buddies for a quick cab to Bourbon Street, site of triumphant conquests two of the past three nights. On Monday, girls promoting Hawaiian Tropic suntan lotion, breasts a-poppin’, sandwiched you for publicity photos, and you straggled back to the hotel at four a.m. The next morning, you were late for the team meeting, and Coach Ditka threatened to fine your roomie Becker $1000 if he let it happen again. Tuesday night, Becker tucked you in by six o’clock and fed you a sandwich at midnight. By Wednesday morning, you were telling the assembled scribblers at your press conference that it’s so “crazy down here” you planned on locking yourself in your room for the next four days. Uh-huh.

That night, while you dined at Felix’s Restaurant and Oyster Bar, an impromptu horde chanted, “Rozelle! Rozelle!” outside the restaurant, gifts were sent your way (Guinness stouts, headbands, T-shirts, kisses, Super Bowl key chains that beep when you whistle), and you welcomed to the group a sunglassed, mustachioed madman in a flowered shirt who had boozily burst into the restaurant with a soul brother in a bear suit and approached you at a hundred decibels with the words “How you doing, pal? Thanks for shopping New Orleans. Tee it up! I’m even sicker than you are! I’m a nobody! I’m the biggest asshole! My name’s Chris, and I can’t miss/After I look up your girl’s dress/But I didn’t come here lookin’ for trouble/I just came to do the Super Bowl Shuffle!”

This dude would keep the flies off you, you figured, and soon he was shooing away picture hounds, pushing people around and screaming: “Put an egg in your shoe and beat it, fella! See you round like a doughnut.” You laughed into your beer: “I love this kind of language. Violence! Got to have violence. Life is not complete without violence!” Chris would escort you and your lawyer and your field-goal-kicking friend Kevin Butler (“Butt-head!”) out of Felix’s, and though the press reported the next day that you rudely did not sign autographs, you were polite enough to inform a hanger-on to move his feet lest his sneakers get splashed by the warm trickle emanating from your insides and falling into a Chartres Street doorway (you don’t buy beer, you rent it), while at the same time a bald Washington Post reporter — Kojak, you called him — aggressively inquired as to your diet: “Did you eat oysters? The waitress said catfish? Was the catfish boiled or fried?” The nation waited for an answer, and so did Kojak, pen in hand, standing by a little stream on Chartres Street, as you walked away.

But that was a long time ago. Twenty-four hours. Since then you have mooned a hovering chopper at practice, while wearing an acupuncture headband, and have incited bomb threats, death threats and a marching squadron of picketing feminists, civic boosters and Patriots fans by not saying that New Orleans women were “sluts” and New Orleans men “idiots,” though local sports hack Buddy Diliberto spoke to the contrary on the evening news. And tonight is only beginning.

You stride into the 544 Club, where a Scatman Crothers type in an orange leisure suit and an Adidas headband is laying down rhythm & blues. He sings “The Boys Are Back in Town,” and you join in. A dark woman who says, “You are the shit!” begs for a kiss. Becker smashes a glass at the feet of Chris the Nobody for no reason other than that a six-foot-five, 267-pound football player who’s on injured reserve and hasn’t played in months gets a little glandular now and then. You say over the screeching saxophones: “You’ve got to teach your body who’s boss! If you’re feeling down, go out and abuse it again. If you don’t test your body, it will never learn how to respond.” This is why you hang off Waikiki Beach hotel balconies and swing from floor 24 to floor 23. This is why you drive down a twisting two-lane highway and close your eyes and see how far you can go without opening them. This is why you drink after a drunk. A man walks by and asks, “How’s your ass?” You’re the most famous sore ass in America.

Out on the street again, you’re swarmed by the crowd. You jump onto lineman and buddy Keith Van Horne, a six-foot-seven, 280-pound bruise brother, who gives you a high-speed, no-nonsense piggyback ride down the block. You end up at Pat O’Brien’s, a raucous institution of alcohol, and though hundreds wait outside the club, you’re in because you’re you. “Sign my tits,” begs a woman, her husband on a tethered arm, both in number-9 jerseys. The pen’s ink blurs on the jersey, and you laugh: “They gotta be firmer.” The club, meanwhile, is in chaos. The piano lady stomps through “Bear Down, Chicago Bears.” (There are telephones on sale these days that, instead of ringing, play “Bear Down, Chicago Bears.”) You sign your name and number. Again. And again. The crush tests your body. The waiters give up.

When you leave with Jim Kelly, a star quarterback in the USFL, you push down a long corridor of fans and enemies to the street. You turn down Bourbon. Every time you stop for a kiss or an autograph or a photo or a compliment, a reservoir of curiosity and worship builds around you, until you burst out again and stride down the street. Kelly yells: “Hey, this is what you dream about! You wouldn’t want it any other way!” By the time you reach Kelly’s hotel, an undercover cop is running interference for you and your entourage, and the tide of fans sweeps through the hotel doors, A Hard Day’s Night gone jockstrap. You make it up to Kelly’s suite, and a food fight erupts to the beat of a ghetto blaster, until you get restless. At which point you and Kelly head for the wrought-iron veranda and take aim at Bourbon Street revelers with oranges and apples. You never have this much fun throwing at practice.

■

In the orchards of San Jose, California, when you were just a boy, you’d sit in the trees and throw handfuls of prunes at the windshields of passing cars and trucks. Seems like as far back as your mind goes, there was trouble. You remember in “kinnygarden” the principal picking you up by the shirt and slamming you against the wall. Even before that, you remember being tied to the legs of the kitchen table. “Me and my brother would always fight,” you say, “and Mom couldn’t watch us both, so she’d tie us to different ends of the table. Like dogs. My dad would come home and say: ‘Untie them! They’re not fucking animals.’”

No, not an animal. But a hyperactive kid growing up under the thumb of strict parents, growing up without money in a family of eight on the black and Mexican side of town. Now that you’re famous, every fifteen minutes the press explains the constant sunglasses — at age six you were trying to unsnag a leather holster strap with a fork, to better access your toy gun, when the fork flew into your eye, which you almost lost and which still hurts in bright light — but they don’t mention that you waited six hours to tell your mother about the accident, so fearful were you of a beating. You had improperly used a fork out of her kitchen. These are the private subtleties.

There’s public record of the rest. You were a minor vandal, a little pain in the ass to teachers, who slapped you — only to be slapped back — and above all, you were mean. “Every day at lunch I would run to the playground gate and lock it on the crippled girl,” you recount. “She had crutches, braces on her legs. The easiest way to get her was to make her climb that playground fence. Her house was only fifty feet away. She’d have to climb over the fence, and she’d get caught up, she’d be screaming, ‘Mom! Mom!’ I’d stand there and wait till her mom opened the door, and then I’d boogie home. I don’t know if I was mad at the world or bored or what. I was not a nice little kid.”

But you could play. Anything you tried — basketball, baseball, football. You were cocky and rebellious, like Namath, your hero. You always liked “his style, his white shoes, his attitude. He did his own thing. They say he was a playboy, that he drank too much, but on Sunday he won.” And like Joe Willie, you didn’t care for the authority of coaches or institutions — you were from that first generation of post-Nam high-school jocks who grew up playing stoned and rocking hard, who said later to all that Knute Rockne crap — let’s have fun and kick some ass. And your playing was a ticket to college. You wanted to go to Notre Dame, but they didn’t recruit you. Maybe you were too small. You thought about going to all-black Grambling, just to be different. But you ended up at BYU, where things got stranger.

Brigham Young University, in Provo, Utah, had a reputation for throwing the football and was near your home in Roy, where the family had moved during high school. Those were the pluses. The minus was that you were raised “a fuckin’ Catholic” and BYU was ninety-eight-percent Mormon; socially, the school is slightly to the right of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. This is the place where you had to sign a paper pledging not to smoke or drink or use drugs or have sex. “You couldn’t even beat off!” you joke. This is the place where the national anthem is played on loudspeakers at eight a.m. and five p.m. across the campus, prompting students to stop on a dime and stand in holy observance. You kept walking ’cause you were always late. This is the place where they caught you with a beer on the golf course the summer of your freshman year. For that you got probation. From that came a firm commitment to raise hell. “But,” you say with a wink, “I had to raise it very discreetly.” This is the place where the campus CIA had you under surveillance (the sex police watched the dorm, compiling intelligence on who was zoomin’ who). It got so bad you used to send your steady, Nancy, out for your chew and your beer. “Everyone in town thought she was the alcoholic,” you say, laughing.

You didn’t buy into the “student-athlete” trip during your five years in college. You worked hard on cultivating your soon-to-be-legendary laziness. You tried one job — shoveling dung for a farmer — and that lasted quite a number of minutes before you said, “Bullshit on this.” Squeaking by on scant scholarship money and Nancy’s earnings as a hairdresser was more up your alley. One summer you were so poor, you and your wide-receiver buddy Danny “Pluto” Plater lived off a cherry tree in the back yard. “We ate cherry pie, cherry cobbler, raw cherries,” you say. “Hey, you get hungry, you go to the back yard.” So you survived at BYU, tooling around in your beat-up Dodge Charger, wearing your platform shoes and your brown and white checked polyester jacket, listening to Tommy James and the Shondells sing “Crimson and Clover” over and over. You were too poor for new records. You were too bored to study. You didn’t graduate.

What pissed you off most about the place was the hypocrisy. “People were always pressuring you about the church,” you complain, “and saying you were being bad. But there were all these Mormon people high up in the administration doing things in the fuckin’ closet that nobody knows about. I couldn’t stand the fuckin’ place. My best moment at BYU was leaving.” Before you did, you set seventy-one NCAA records for passing and total offense and won yourself all-American credentials. You were being bad.

■

Two days before the super bowl, you’re holding Mr. Meat, a marital aid with a hand crank. You were playing around with a bunch of bananas during a photo shoot at a rented house when one of the women who’d gathered to watch gave you the dildo as a prop. The Bears have made it clear that they don’t want you to do the photo session (with or without dildo). You don’t care what the Bears say. In fact, your true football dream is to play for the Los Angeles Raiders. In fact, you and Bears coach Mike Ditka have had words plenty of times this season. Most of his words have been along the lines of “Shut up!” To the voracious press, which flits from media event to media event down here like a school of stupid piranha, Ditka has taken to merely saying, “Jim is Jim.” As if that explained everything. Funny, that’s what your college coach ended up saying.

Jim being Jim now involves fondling Mr. Meat with Becker and Van Horne while singing “A Love Bizarre.” (You prefer Cougar, Springsteen, Talking Heads, but you’ll deal with whatever’s on; despite the early-season skinhead-with-shag razor cut and some familiarity with the Sex Pistols, you’re not much for punk; you’re closer to heavy metal — why, you just saw Dee Snider the other day, and now your agent is going on about how Jilted Lady or, uh, Wicked Sister is one of your favorite groups.) So Mr. Meat is being man-handled, and this brings to mind the TV interview you did a few weeks ago when they asked you what you’d been up to while you were out hurt. You showed them a copy of Hustler. You love doing to the press what you are currently doing to Mr. Meat: dicking it around.

This stops abruptly when the woman who fetched Monsieur Meat announces that it is not her property but rather that of an unidentified man. Instantly you begin wiping your hands on the jerseys of Van Horne and Becker and shouting: “Oh God, burn my hands! . . . My fucking hands! AIDS in the NFL!” This is the one story angle the press has not used this week.

You and the boys run to the head to wash, thoroughly and with soap. (This is serious.) You come back without Mr. Meat but still in your blue Frederick’s of Hollywood G-string. This useful item allows you to take acupuncture treatments for your sore buttock without removal of undergarments. In fact, it’s all you had on this morning when Hiroshi Shiriashi went about his needlework. You were just getting up and let go a bit of gas, as is your habit. Hiroshi, with Japanese tact, replied, “Oh, no like back window during treatment.” But the best thing about your little G-string is that it has a lock in front, and only one woman has the key, and she is the best woman, with her big brown eyes and her long blond hair, and she is your woman, with her shades and her Madonna smile, and she is the woman, and she is coming to town tomorrow. Ya-hoo! And she’s bringing the kids.

“Nancy,” you have said more than once of your wife of four years, “is the best thing that ever happened to me. I knew at BYU she was too good for me to lose. She helped me survive that place. She has kept me alive. I would be on Rush Street in Chicago closing down the bars every night if it weren’t for her. She put me right in my place, and now I’m just taking up space. I’d be dead without her.” Nancy has made a home for you, in a town house in suburban Chicago. (Your dream house is in the planning stage — land acquisition, architect search, et cetera.) Nancy cleans the house and cooks the meals and mothers the kids, without help and because she wants to. She packs your lunch every day in your leather briefcase, which you tote off to work (practice) — two sandwiches, plus Ding Dongs or Suzy Q’s for a late breakfast. She has decorated your house in an early Toys ‘R’ Us manner — there is a slide in the living room — and she lives for you and the kids: Ashley, two and a half, and Sean, fourteen months. She’s the one who taught you how to put mousse in your hair.

You love to come home and play with the kids. Sometimes Ashley calls you Jim and brings you a little piece of paper with a pencil, begging for an autograph. Her journeys with Dad outside the house have convinced her that this is appropriate behavior. When you’re away, she kisses your Sports Illustrated poster on the wall. You wanted a girl first. You like to take her into the locker room with the words “Let’s go see some naked boys.” Sean too is a reason for celebration. On his first birthday, some teammates came over and drank a shot for each month he’d been on the planet. Past twelve, you started toasting Generals Patton and MacArthur. It was a Boys’ Night In.

After you put the kids to bed, Nancy pops your favorite microwave popcorn and you sit up in this big old recliner and watch your TV, clicking between channels, sipping your Mountain Dew, maybe watching your favorite Nicholson flick, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which Nancy got you for Valentine’s Day. And you just love to hang with Nancy, your best friend, your mother, wife and girl, your rock and your redeemer. This is what you do, anyway, when you’re not walking down Bourbon Street on the front page of USA Today.

■

Eventually, finally, inevitably, there is the game. You win, of course. But you don’t win Most Valuable Player, which the press votes for, because they need you but don’t like you. Maybe if they knew you flew a depressed laid-off steelworker from Utah and his wife down to the game and set ’em up with hotel and tickets, maybe then you’d have been the MVP. Maybe if you’d been more public about buying that poor kid a bicycle when his got stolen, maybe then you would have played better in their eyes. Man, you don’t have time for the press.

But you have to face these know-nothing jock sniffers one last time. You thank your parents on national TV. You do it for them. (Your dad is always asking you to say, “Hi, Mom!” to the camera on the sidelines, but you prefer “Hi, Nancy!”)

Huddled around your podium, the press needs to know the significance of each headband (Juvenile Diabetes Foundation CURE, POW-MIA, United Way, Support Children’s Hospital, and Pluto). Well, you wore the headbands ’cause you like the causes and you love your dear friend “Pluto” Plater, who had to quit football because of a brain tumor. You take the blame for Walter Payton’s fumble, which you didn’t cause. You shock the journalists by saying it was just another game. (How dare you?) You just want to get to the golf course, you tell them. You don’t have any more time for these little snivelers.

As you leave the interview room in a rush, jostled by reporters and stung by TV lights, an old man in a corridor underneath the stadium calls out to you. A black man in a blue suit, he calls out, “Jim, please. . . .” You stop, turn around and see him, legless, a stump in a wheelchair. You walk back to him and he reaches out to hug you, his eyes going watery. You lean over and hold him. This you have time for.

■

Out by Kahuku Point, on the far side of Oahu, you’re fixing to play a little pasture pool to the tune of the beating blue-green surf. Eighteen luscious Hawaiian holes for the March of Dimes, a celebrity charity thing. You and the other NFL all-stars have been sent out for a week of practice before the Pro Bowl, and this is part of the preparation. It’s a tough job, but somebody’s got to do it.

Clad in natty country-club wear, everyone rides the course in carts, but you will walk it barefoot, wearing only shorts, Revo red-tint shades and a sunburn. The women in the gallery are happily scandalized by your outfit (or lack thereof), the men slightly confused. Of course, the ultimate goal of your life — the grand design — is to buy a golf course so that you can play naked.

On each green, well-meaning souls offer you sunscreen. You are not interested in sunscreen. You are interested in the beer cart, which is playing hard to get. It appears so infrequently that you find yourself scarfing two or three Buds at a time, protecting yourself from scarcity a long par-5 down the line. Whenever you roll a putt short, which is often, you scold yourself: “All right, James, take your panties off and hit the ball!” You have a reputation as a club thrower — you were swinging so poorly one day you threw an iron and nearly hit Nancy, who now shuns golf as an act of self-preservation — but today, even after a wimpy drive in front of a big gallery on the first hole, you hang on to your driver.

Roy and Herb and Don, the three middle-aged men in your foursome, who have paid a pretty penny to play in this event, seemed pleased to be with you. You call each “tiger” and “partner” and compliment them on their games when you are not fueling up (ten brews over eighteen holes) or spitting tobacco on the greens (take that, Ben Hogan!) or posing for photos along the fairways with voraciously tanned ladies glinting with Rolexes and marbled in cellulite, as well as tag-along teenage punks in ratt and kiss T-shirts armed with VHS cameras. Already, your emergence as an antiestablishment Establishment icon has begun to produce odd overtures from strangers. As you munch on a waffle dog under the lilting Hawaiian sun and wait to tee off on the fifth hole, a man carts up to you and says: “Hey, partner. I’m delighted to see another crazy in life. And willing to speak your piece. I was in the air force for a year, strung out on smack. Now I’m a director of development for the March of Dimes. Man, the way you use your physical ability to capitalize. You don’t take shit from nobody. At least I assume you don’t. Right on!” Fore.

You smack a long drive. It feels good. Golf is your passion, football only your profession. “Football is not a nice game,” you say. “Football is a sick game. There are people out there trying to maim you for life.” And in your case, they’ve almost succeeded. In addition to the broken bones, tendinitis, muscle spasms, bad back and four knee operations, last year you suffered a lacerated kidney in a game against the Raiders. You could have died on the field.

When a man comes to you, desperate for an autograph but with nothing to sign except a deck of cards, you sign the joker.

On the way back to the Honolulu hotel where the NFL has stashed its beef for the week, you’ve got some time to reflect on life. You are not by nature a reflective guy; you are more a man of . . . not action but reaction. You wait till they make a rule, and then you laugh in its face. Like when Coach Ditka told the players to wear shirts with collars on your first road trip your rookie year and you came on the plane in a backless T-shirt with a priest’s collar attached.

But now you have bigger decisions to make. A number of people are asking you to be James Dean in cleats. You’ve been offered roles in a lot of movies. You’ve turned down a guest-VJ slot on MTV, a role on The A-Team and a spot hosting Saturday Night Live. “I hate acting,” you say, riding along Oahu’s eastern shore. “I like being myself. I don’t want to pretend to be someone I’m not.” True, you did the Coke commercial, but that was for Coca-Cola Classic, which has always been you. “That new shit is nasty,” you explain. Oh, and you’ll do a quickie book ’cause the coin is so outrageous — something like a quarter mil — and a Miami Vice appearance, but only if they let your linemen come along. So there are some fringe benefits, but on the whole you’d trade this stage for the wings any day.

You think: “I can’t go anywhere now and not be bothered. People never go up to the president of IBM and say, ‘Can I have your autograph?’ I got people all over calling me — saying they’re my cousins or we’re distant relatives. When you go out, you can just feel these people beating down at you, staring at you. Let me tell you, whoever said, ‘It’s lonely at the top,’ was speaking the truth.” You spit a plug out the car window and continue: “I mean, we’re fuckin’ world champs and it don’t feel like shit! I thought this was gonna be the greatest thing in the world. I thought I would feel like going bananas for a month. But to me, well, shit, we gotta do it all over again next year. You work your ass off all year long to get there, and you do it, and then it’s over.”

When you get back to the hotel room, Nancy runs out, bringing back a fast-food supper. While you eat your Big Mac in Hawaii, McDonald’s is calling your agent in Chicago, hot for a commercial. On the coffee table, next to your fries and shake, is a gift from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation. It’s an elaborate flower arrangement — an explosion of red obaki, green plants, balloons and, hidden in the flora, five bottles of Coors. With it, a note: “You will always be our hero. What more can we say?” Nothing. You’ll drink to that.