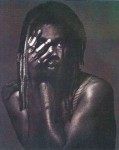

Vernon Reid

VOODOO CHILD: the rolling stone interview with living colour’s Vernon Reid

VOODOO CHILD: the rolling stone interview with living colour’s Vernon ReidRolling Stone

July 8-22, 1993

A matterhorn of cassettes twists above the couch: Paul Simon, Patti LaBelle, Keith Jarrett, Yaz, Little Richard, Gang of Four, Miles Davis, Morrissey, Rush, the Pretenders. On the shelves, the Star Trek films fight for space with Blue Velvet, The Maltese Falcon, Malcolm X: Highlights of His Life and Speeches, Sid and Nancy and House of Games. This month’s supply of comics — Doom Patrol, X-Men, Namor, Animal Man and The Silver Surfer — does battle on the coffee table with a copy of Consumer Reports (testing tires!) and The Portable Curmudgeon.

Information overload, indeed. The overstuffed living room of guitarist Vernon Reid, like the overstuffed mind of Vernon Reid or the overstuffed solos of Vernon Reid, presents a complex splatter of high-minded intelligence and visceral vengeance, boot-stomping adolescence and abstract imaginings. Perhaps this is to be expected from the Jackson Pollock of electric guitarists.

I’d come to talk to Reid because he and his band, Living Colour — with vocalist Corey Glover, drummer Will Calhoun and now the wickedly good bassist Doug Wimbish — had made by far their best record, Stain, and I figured it was time to find out wha’zup with him. I’ve known Reid since the fall of 1981, when he was playing with Ronald Shannon Jackson’s Decoding Society and I was put in charge of sound on a European tour. Perhaps since Reid knew I could turn his level down at any time (at least to 10), and he had something like seven guitars on the tour and no one to help him carry them, we became friends. I ended up producing a few records for the Decoding Society and then, in 1985, Reid’s first under his own name, Smash and Scatteration, his collaboration with Bill Frisell. After that we drifted out of touch, though he’s been a frequent two-dimensional visitor in my house ever since MTV got ahold of “Cult of Personality.”

Stain, vicious and nasty yet somehow insistently lyrical, is at once the sparest and richest of Living Colour’s records. It’s also easily the darkest. Whether or not this might have anything to do with the recent breakup of Reid’s young marriage remains hypothetical. Because although he speaks of stepping off the sociopolitical soapbox he’s been on since he cofounded the Black Rock Coalition — to better address more personal issues — in truth, Vernon’s still uncomfortable talking about emotions that hit too close to home. In the midst of our conversation, his estranged wife rang the bell. She’d come home to look for something she’d left there.

Of course, there are good reasons for Vernon Reid to stay on the soapbox and to keep playing his guitar in as excoriatingly righteous a manner as possible. After the interview, when I got into the hired car that had been waiting to take me back to Manhattan from Reid’s Staten Island home, the driver said: “I wouldn’t want to get stuck in this neighborhood. It looks pretty bad.” And then he asked, “Is he white or colored?”

“Neither,” I said.

If an alien came down and asked you where you came from, what would you say?

The planet Brooklyn.

During the recording of ‘Stain,’ the cook at the studio listened to you take a solo, and then said, “The people from your planet will be very happy with you for that.”

[Laughs] Yes, they will be very pleased. Hmm . . . Where am I from? It’s interesting, on the one hand I’m from a family that is very close but small. Me and my two younger sisters are each five years apart, so my youngest is ten years younger than me. So I spent a lot of time by myself, ’cause I wasn’t able to really communicate. I’ve always felt like I’ve been in a strange place. My parents are West Indian, I was born in London, I was raised in Brooklyn, and all of my friends growing up had parents who grew up in the South — and I was affected by their southernness.

Would you describe your background as middle class?

I’d say working class. We lived in an apartment. No car. My dad is still an air-traffic controller, and my mom still works for the hospital-workers union.

How would you say you are like your mom? And like your dad?

They both have a sense of humor. My mom is a really kind person. Really a kindly person, a sweet person.

Are you?

I try, I try. I think I’m empathetic in a way. My father is a real serious person. Really, really serious. He’s always been a real moralist in a way: There’s a right and a wrong. He’s not a shades-of-gray kind of guy.

That soapbox you’ve been on for a couple of years is a strange place to be. I sense you stepping down from it on ‘Stain.’

It was definitely time for that. It’s a funny thing to have always had thoughts in your head, and then suddenly someone gives you a microphone and says, “What do you want to say?” Huh? What? Really? For a minute things got a little pontifical.

But wasn’t it disingenuous on your part, upon the great success of the band with ‘Vivid,’ to carp on the fact that certain people focused on the color of the band, when in fact you had made an issue of it as the spearhead of the Black Rock Coalition and when it’s in the very name of your group?

It depends on the lens you’re looking through. As far as talking about race and America, and race and the music business, I’m always down to talk about it. But when it’s about a band’s music . . . I would go to interviews where, literally, not a song was mentioned. And I realized some people were not interested in our music but just Living Colour as a symbol. It was a long time before I actually understood that. It was almost not what we were doing that was important to some people but the fact that we were black and successful doing it. That, in a way, was like taking the bait.

The first two records, ‘Vivid’ and ‘Time’s Up,’ focused a great deal on external, social issues. The material was not overtly personal. You were, as you once said, “Tossing bons mots on big social issues.”

There are moments of real personal experience on those records, but the most attention-grabbing things are more exterior things. Still, I definitely think it’s headed toward something more personal. We’re not all the way there yet.

What was going on with you while you were making this record? Because it’s a really dark record. I don’t mean in a negative way, because I don’t associate darkness with negativity.

Right, thank you! [Pauses] Let me think about this. [Pauses] There are things, demons, for want of a better word, that have to be looked at in order for you to really change. A demon doesn’t have to be a homicidal thing: It can be the demon of your complacency, the demon of laziness. Overall, I think Stain is about people trying to make sense, one way or another, of this insane, pressure-filled world and dealing with it. In the sense of: What am I going to do? What are my choices? In “Ignorance Is Bliss,” the character knows that there is famine and war, but really he just wants to get laid.

And it’s a good thing, too, otherwise our species would die out.

I don’t think he’s necessarily thinking of procreating. He’s thinking of recreating.

Yeah, but you don’t have to be thinking like a good Darwinian to be one.

I concede the point.

Did it surprise you that so many critics found the first couple of records humorless? That the band’s social observations were unleavened by any sense of irony?

You know, it’s like if you don’t see it, it’s not there. I think there’s a lot of irony in “Which Way to America.”

And I think that’s the best of all the social-observation songs — as opposed to something like “Pride,” which is an earnest anthem.

This is the thing. Different band members wrote different lyrics. “Pride” was written by Will [Calhoun], and it’s heartful. We’ve learned from it. We now are more critical of each other’s lyrics. Before it was like, oh, this is the song that you wrote, and the lyrics were cool because the music was cool.

How do you deal with the democratic as opposed to the autocratic element of this band? You’re in a funny place because it’s your band, but it’s not your band. In the beginning it was, literally, Vernon Reid’s Living Colour. It was your brainchild, as much position paper as band.

I decided that I wanted it to be more than my trip. And there are times when it’s frustrating, I won’t lie to you. Because you have to deal with everybody’s aesthetic, not just your own. And sometimes that’s good. I’ve had some pretty harebrained ideas that on balance wouldn’t have worked if Corey [Glover] hadn’t just said, “That sucks.” It’s a real danger when things are completely autocratic.

But how do you deal with the conflicts?

We argue. We argue. We talk about it and talk about it and talk about it.

And the last man standing wins?

Sometimes. Eventually, somebody concedes, because they rethink their own position, or they just say, “Fuck it.”

You always seemed to me to have a very strong feminine side to your personality, which is interesting in the context of Living Colour because your crossover is really one of age and gender. Your audience is almost exclusively young male.

Yeah, it’s male, but there’s very little machismo in what we do. There’s not a lot of “dirty deeds done dirt cheap” kind of vibe. I don’t think of what we do as a male “acting out” kind of thing.

Why don’t more women like your music?

Hmm. [Pauses] I guess because it’s hard and crazy. I guess it doesn’t push those buttons.

You say that as if you’ve never thought about this, which I find hard to believe.

I don’t know. I’m not a woman. It’s presumptuous of me to assume a position which I cannot biologically attain. [Laughs] I know women who dig it, I know women who don’t dig it. Whenever I have seen women in the audience, I’ve always been intrigued. Like a woman in the middle of the mosh pit, that’s interesting. Maybe it’s because the music is about releasing a kind of aggression, a kind of cathartic release of aggression.

Speaking of age as well as gender: You’re getting older, and the audience will get younger unless your genre changes. Does this ever strike you as interesting or curious?

I don’t really think about it or dwell on it. I just try to stay open. Maybe as I get closer to forty, I’ll think about it differently, but for now I just am where I am. It’s sort of like where I am is where I’ve been for a very long time, so I don’t think about it.

Why doesn’t the music appeal more to your peers?

I guess because the songs aren’t really about being settled in your life. We’re dealing with situations that are changing underneath you and around you all the time and struggling with your feelings as they’re changing.

Whereas Sting and Paul Simon have older audiences.

It’s like in “Graceland,” the line “My traveling companion is nine years old, he’s a child of my first marriage.” That is a wonderful lyric. That’s not something someone fifteen is going to relate to. But when I’m writing a song, I don’t think about any of this stuff. It has a powerful resonance in the Paul Simon song because he’s come to that in his life. In an older audience a lot of people have been divorced and have those kind of trips with kids from their first marriages, and it speaks to them in a way that’s so direct and so piercing — that’s why it works.

Let’s talk about your peers, like Public Enemy. Now I like what you said to Axl Rose when you played with Guns n’ Roses at the Rolling Stones shows in L.A. in 1989: “If you don’t have a problem with gay people, then don’t call them faggots. If you don’t have a problem with black people, then don’t call them niggers.” But if you don’t have a problem with women, why play on a PE song called “Sophisticated Bitch”?

There were no lyrics on it at the time.

And if you had known?

Maybe not.

What about the wholesale misogyny of most rappers?

I don’t like it. I think it’s callous. And it perpetuates an idea that was started a long time ago, that keeps the black family destroyed.

When the song came out, your defense was that the song was about a particular kind of woman that everyone has had to deal with. But it does seem that since you are so careful about language, and that words are deeds, it was a bit of a double standard.

It probably was. But it is true there were no lyrics.

Did you call Chuck D when it came out and say, “How can you do me like this?”

[Quietly] No, I didn’t. I didn’t.

And being interviewed by ‘Penthouse’ doesn’t bother you on the feminist tip?

No, it doesn’t. It really doesn’t. There is credible writing in Playboy and Penthouse.

What if there was a terrific magazine, with fabulous writing, whose only weak point was that in its photo spreads every month it depicted blacks as lazy, shiftless, watermelon-eating niggras?

That would be a problem.

So I’m shooting down the “good writing” defense. What’s wrong with saying you like eros and there are limits to the PC thing?

There is a difference between photos that depict violence toward women and photos that don’t. I don’t think theirs do.

Do you worry about the image that rap broadcasts to the white suburban audience, which is the largest consumer? That is, the new myth of the inner city as Wild West — the gunfighter, the outlaw, now carrying an Uzi and wearing colors. It’s a new racist stereotype.

I’m worried more about the actual reality of violence in the black community. The amount of violence and murder. To the degree that gangster rap is really insensitive to the loss of life of our own people, that’s really what concerns me. Not so much suburban teenagers’ response to it.

But I know you are sensitive to how racist mythology gets built up and how imageering can have nefarious effects.

Absolutely. It’s a problem. It’s a problem for me on a number of levels. I’ve heard all the arguments for using “nigger this” and “nigger that,” and I don’t buy any of them. Malcolm X actually refused in any of his speeches to refer to blacks as niggers. He wouldn’t do it. And he really got to white America when he started calling them white devils. That struck a real chord of fear and pain in white America. That is the only thing that even approaches the kind of pain and damage that nigger has done to African Americans.

So why are your brethren so anxious to appropriate the word? I know appropriation is postmodern, and by appropriating you supposedly defuse the power of it.

That only works if the historical conditions are no longer at work. I’ve heard arguments about the recontextualizing of the word, and how you can change what the word means. But when brothers are killing one another, that’s what it’s all about: It doesn’t mean anything, because it’s just “another nigger dead.” You can’t argue that by recontextualizing the word, nigger becomes a term of affection, when at the same time, in the absence of white people, it is still a term for the complete disposability of another human being. Which is what it is, right now, no matter what people are saying about it.

How do you feel about Ice-T?

How do I feel about Ice-T? [Pauses] I think he’s really smart. I’ve had arguments with him about this. One of his responses to me was like “I know white people are thinking this about me anyway, so I just call myself that.” And my big problem with that is, look how much empowerment he’s giving to white people and their opinion!

By letting whites set the terms of the debate.

Exactly. So what white folks think becomes the beginning and end of the perception. And I think that is wrong.

Speaking of which, I wonder why you’ve never been involved with Spike Lee.

We know each other. You don’t have to like everything he does. There was a time when you just couldn’t criticize him, because he was, like, the only one out there. And that is no insignificant thing. He’s an important filmmaker.

How did you like ‘Malcolm X’?

I didn’t see it.

I’d like to know what are the arguments you’re having with yourself these days?

[Long pause] I’m having an ongoing discussion along the lines of “What happens when your dream comes true? Does your dream have to change?” I look at everything that’s happened with the band and my career, and to a certain degree, I’m living the dream of a sixteen-year-old boy who started playing the guitar.

In a way, I dreamed of this. I dreamed of meeting Carlos Santana. Recently, he was playing in New York — it was like a jam with Carlos, Lenny Kravitz, Third World and myself. We played some Bob Marley songs and instrumentals. And standing there looking at Carlos, I felt a fullness in my heart. It sounds corny. I was standing there remembering how Santana’s Caravanserai changed my life. I started playing guitar because I heard “Black Magic Woman.” Those moments are the things that I live for. The feeling that you’ve come into yourself, you’re connected. I felt it while making Stain. It’s a strange and humbling thing. I was riding a bicycle up at Longview Farm, where we recorded. I was doing my circuit, and I started riding up the side of this hill. There was all this open space. And I had this overwhelming feeling of connection to everything. I thought my head was going to explode. I’m not a New Agey kind of person, but I can’t deny that I felt this thing. It’s probably because I was hyperventilating [laughs].

Do you ever feel guilty that you get so much attention, and you know so many master musicians who are obscure and scuffling?

I feel that the system is unjust in the sense that one person gets signed and another person doesn’t. Guilt about it is limiting and will eat you up. I feel more anger at a system that would ignore the obvious talents of so many musicians.

You’ve spent enough time on the subway in the middle of the night that I wouldn’t think the limo would bother you too much now.

No, it doesn’t. That’s a funny thing about being in this situation. I feel like I’m a tourist in the house of fame. We won a Grammy, and I was on the subway the next day. I was standing there straphanging, and a guy turns to me and says, “Didn’t I see you on TV last night?” And I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “Well, what are you doing on the subway?” And I said, “I have to get up to Fourteenth Street.”

You are a guitar hero in a traditional sense, as opposed to, say, the Edge or Bill Frisell, who are sort of guitar anti-heroes. Do you ever resent the baggage that comes along with the role of guitar hero?

I feel closer in spirit to Bill Frisell than I do to traditional guitar heroics. It’s a funny thing. We are in the age of super-chop guitar playing. It’s amazing what really young players are playing. Amazing stuff. There’s a lot of division within the guitar community on whether what I’ve been doing is valid or where it’s coming from. And I’m just doing what I do.

I still sense some unease with the role. On all the Living Colour records, there is not one long solo. You are someone who is more than capable of bringing that off.

Part of it is, on the record the songs are more paramount than the guitar solos. I get a chance to play a lot, even if it’s in snippets. On one level, brevity is the soul of wit. If you can say something in a few bars, say it.

Do you think you can take the guitar to that place where Coltrane took the saxophone or Miles Davis took the trumpet?

I want to take it to a place when I’m playing where there’s no up or down, there’s no left or right, there’s no good or evil. Where the form disintegrates, where the genre disintegrates, and I can float freely, and it works. And it works not only for the song but for its own sake. That’s really the goal of my improvisation — to go to that place. The juggler who stands on one leg and sings.

What do you feel when you read something like what ‘Melody Maker’ wrote about ‘Vivid’: “One feels the source and destination of their music is nothing more profound than a desire for self-exhibition”?

Well, on one level that’s the risk that you take, and on another, that’s just English nastiness. [Laughs] There’s a real prejudice there against musicianship. The punk ethos of “anyone can do it” does not extend itself to musicians who can improvise.

Has there been anything you’ve learned from the critics?

Part of what’s going on is that the genre is a hated genre. The only decision is how are you going to put these people down. Part of it is that people don’t listen. “A man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest.”

But have you learned anything?

Yes, I have learned. I’ve learned about how didactic the band can be, and that has made me think. I’ve learned that earnestness is some sort of crime.

It’s important in human beings, but it’s deadly dull as an artistic strategy. Like at the end of your home video ‘Time Tunnel,’ which is essentially a marketing tool for selling the band, you talk about how much you’d love to change the world. God knows, wouldn’t we all?

I can always deal with intelligent, thoughtful criticism. But the vitriolicpissiness — the legless man who tries to teach others how to run — no.

Let’s turn to the subject of class as well as race. I was on a river trip in Alaska, and on my raft was a well-to-do white stockbroker’s teenage son from Greenwich, Connecticut, who was, amid the glaciers and the grizzlies, intently listening to ‘Time’s Up’ on his Walkman. Is it strange for you, emotionally, intellectually, that you’re more likely to get to him, that upper-crust or middle-class white kid from the suburbs rather than to the black kid from the West Side of Chicago in the Henry Horner Homes?

This is a funny question. I went to see Albert Collins at the Apollo Theater, up in Harlem. I walk in, and the audience is two-thirds white and one-third older black people, and at least seventy-five percent of that one third are in their forties. This is the sort of thing that jazz musicians and blues musicians have just had to come to live with, unfortunately. When I see black people in the audience, of course I feel really good about it. But I feel good about everybody that comes to see it. The problems are really about exposure and access. My biggest problem is that so much music is not heard — the kid in the projects is not being exposed to a lot of things he should be exposed to.

Well, he can change the dial on his radio and listen to the station that is playing your music if he liked it. But chances are he doesn’t like it.

Chances are, yeah.

Is it ever difficult for you, personally, to deal with this?

Yeah. But I never thought Living Colour was going to be mass-appeal black music to begin with.

Why shouldn’t it be?

Our relationship to rock & roll music is peripheral at best. Everybody started digging Hendrix in the hood only after he passed away.

Have you vanquished Hendrix’s ghost?

I don’t want to vanquish Hendrix’s ghost. Hendrix moves over this music in a lot of ways. He’s one of the people who took Bob Dylan’s influence as a songwriter and combined that with his R&B and blues roots and really went somewhere with it. The thing about Hendrix that influenced me is his sense that “anything is possible.” Anything could happen. Whatever happened when he put the guitar on was meant to happen. That is the amazing thing about Hendrix. His process is a mystery, a complete mystery. Playing in Little Richard’s band — and in the course of a few months, a week, a day, he’s just reinvented everything.

At the top of your stairs, there’s a picture of Hendrix, which you see whenever you walk into your music room. Do you take that to be inspiration or responsibility or both?

I’d say both. There’s something about making your mark. I don’t know what that is for me. Whether it’s with this band or something around the corner or just above my head.