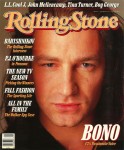

Bono

Bono: The Rolling Stone interview

Bono: The Rolling Stone interviewRolling Stone

December, 1987

“Darling, I would love to take you by the hand, take you to some twilight land,” sings the country songwriter, his voice wistful and cracked. He struggles through the verses, faltering a bit, forgetting, humming here and there, just pickin’ his guitar and tappin’ his foot gently in the corner of the darkened room. Finally, in a mood of wizened woe, he finishes the last chorus, “Am I left to burn and burn eternally? She’s a mystery to me.”

Now, what makes this particular moment in the history of tearful country ballads (a man, a guitar and PAIN!) a bit more fetching, is that the lonesome critter over there in the corner, the sad-eyed young man who done wrote the song, who is sitting quietly at home in his modest castle — which is, in fact, an ancient seaside watchtower built with seven-foot-thick walls of granite and oxblood mortar to withstand shelling from hostile navies — happens to be the same fellow who usually spends his time fronting the world’s most popular rock & roll band.

And when done crooning “She’s a Mystery to Me”, the strange and lovely song he’s writing for Roy Orbison, he launches into “When Love Comes to Town”, an uptempo chugger he figures might fit B.B. King. Barely pausing, he plunges into “Prisoner of Love”, which features a handy doo-wop break in the chorus, and then assays his beloved ballad “Lucille”, his first-ever country song, written way, way back in the spring of 1987. And so here we have Bono, at home outside Dublin, during a short break on a long tour. Well, shucks!

We met a few days earlier in Cardiff, Wales, where U2 gave a spirited outdoor sing-along for 55,000. (Angst ridden and angst driven, the band’s shows have become — for its fans — forceful, friendly rituals; sort of like Up with People, with an edge). Immediately thereafter, a police escort whisked the band members away from the exiting mob toward the little white jet — the one with OUT OF OUR TREE TOUR painted on its fuselage — waiting at the airport to bring them home. And there, over the course of two days in late-July, first in my hotel room, with the gulls wheeling and crying outside the window, and then in his watchtower, with John Coltrane’s recording “A Love Supreme” snaking up the spiral staircase, Bono and I talked. He often spoke in little more than a whisper, his voice strained from recording B-sides of singles until early-morning hours on nights offstage. What he revealed beneath his well-defined and carefully controlled surface was an enthusiast in the grips of reason; a wishful idealist stimulated and confused by his own contradictions; and a young man who quite honestly has not found what he’s looking for — and may never. Chances are if he ever does find it, he’ll know it when he sees it, stop briefly to enjoy the view, and move on.

Let’s do a radical thing and go back to before the beginning. Your grandparents.

My grandfather — my dad’s dad — was a comedian at Saint Francis Xavier Hall, in the centre of the city. He was a morose man. So I think this idea of laughing a lot and then biting one’s own tongue is something that runs in the family.

My grandmother on my mother’s side was a really big laugh. Which disguised the fact that beneath her dress, she had a big stick with which she reared, I think, eight kids. She used to joke that the contraceptives, which were banned in Ireland, were intercepted at the post office, and — too late! — another kid was born, another mouth to feed.

My mother was the oldest of her family and quite petite. Really a delicate flower, but she took on the responsibility of bringing up the younger kids.

Both my mother and my father were from the centre of the city, what they call Dubs. My mother was a Protestant, and my father was a Catholic, and they grew up on the same street. Their love affair was illicit at the time. Ireland was just being born as a country, and the Protestant-Catholic rivalry — the bigotry — was at a pitch. But it didn’t mean anything to them. They faced the flak and got married.

It was a bit of a difficult thing to do.

In a mixed marriage the children had to be brought up Catholic. The Protestants made up only about 10 per cent of the population at that time, and it was an anathema to them. My mother decided to bring us up in the Protestant church, and my old man went along with this. So my old man would drop us off at one place of worship and go on to another one. And I really resented that. I was always fighting with him. Always fighting. We were too alike.

Was he a disciplinarian?

He attempted to be. He was a very strict man. But I was one of those kids who was almost impossible to tie down, from the very beginning. People used to — and family people still sort of — put up the cross [crosses index fingers] whenever I come in. They used to call me the Antichrist [laughs]. How many kids on your block were nicknamed the Antichrist?

What’s the first thing you can remember?

I remember having my photograph taken with my brother and not liking it. I was around three years old. I think we had two little leopards, like ornaments on the mantel, and at the end of the session there was only one leopard left, and I was put away for that.

Do you have any idyllic childhood memories?

None at all. The little pieces that I can put back together are, if not violent, then aggressive. I can remember my first day in school. I was introduced to this guy, James Mann, who, at age four, had the ambition of being a nuclear physicist, and one of the guys bit his ear. And I took that kid’s head and banged it off the iron railing. It’s terrible, but that’s the sort of thing I remember. I remember the trees outside the back of the house where we lived, and them tearing those trees down to build an awful development. I remember real anger.

What of your mum and dad and the way they got on?

To be honest, I don’t remember that much about my mother. I forget what she looks like. I was 14 or 15 when she died, but I don’t remember. I wasn’t close to my mother or father. And that’s why, when it all went wrong — when my mother died — I felt a real resentment, because I actually had never got a chance . . . to feel that unconditional love a mother has for a child. There was a feeling of that house pulled down on top of me, because after the death of my mother that house was no longer a home — it was just a house. That’s what “I will Follow” is about. It’s a little sketch about that unconditional love a mother has for a child: “If you walk away, walk away I will follow”, and “I was on the outside when you said you needed me/I was looking at myself I was blind I could not see.” It’s a really chronic lyric.

There was not a lot of closeness, physically?

Not really. I have just found out bits and pieces about my family in the last year or two. Now I want to know. Before I didn’t. Trying to talk to my old man is like trying to talk to a brick wall.

Even now?

Even now. Do you know, the first time he really spoke to me was the night of his retirement from the post office. I went to his send-off party. I used to hear all the names, Bill O’This and Joseph O’That, and I never knew who they were, and I didn’t really know what he did. But at this party a year and a half ago, I met all these people. And they were amazing. It was at a pub, and there was a guy with a fiddle, and they were all singing songs. There was a guy who had painted on a Hitler moustache who introduced me to his daughter, and I said, “Who are you?” And she said, “The Hitler youth.” It was like a Fellini movie. It was a world, a world of Irish in Dublin. And afterward, he showed me the place he worked, where I had never been. And he showed me the seat that he used to sit in. And already someone else had moved into that seat. And that night, I got to talk to my old man for the first time. We had a glass of whiskey, and he began to tell me a few things about what it was like growing up.

It’s been said that artists never get over their childhood, and perhaps, in some ways, it’s because they don’t that they remain artists.

I think maybe it should be said that a lot of artists never grow up [laughs]. I think it’s certainly true in rock & roll. Rock & roll gives people a chance not to grow up — it puts them in a glass case and protects them from the real world of where they’re gonna get their next meal. Who is it — Camus? — who said “Wealth, my dear friend, is not exactly acquittal, just reprieve.” But in the end, I don’t know if being a pop star is any less real than being a city clerk. Is suburbia the real world? Is the real world half the population of Africa that is starving? I haven’t worked it out yet. I always wondered, “What am I? Am I Protestant or Catholic? Am I working-class or middle-class?” I always felt like I was sitting on the fence.

Well, the very fact that you were 15 when you lost you mum and yet can’t remember her suggests that there is a lot that you’ve blocked out. When you were a teenager, you were very angry and uptight, and I wonder how much of that is a result of her death.

I don’t know. As I’ve said before, the fact that I’m attracted to people like Gandhi and Martin Luther King is because I was exactly the opposite of that; I was the guy who wouldn’t turn the other cheek.

Let’s say you scuffled a bit.

[Laughs] “Scuffle” is a beautiful euphemism.

OK, you beat the crap out of people.

Well, I’d never start a fight, but I’d always finish it.

You were a contentious little S.O.B.

It was the way we grew up. Street fights were just the way. I remember picking up a dustbin [garbage can] in a street fight, and I remember thinking to myself, “This is ridiculous. I’m not going to hit someone with this.” And right then, this guy came up with an iron bar and brought that iron bar down so hard on me. And I just used the lid to protect myself. I would have been dead, stone dead, if I hadn’t had that thing. But when you’re singing songs, people think you are like the songs you sing about. I think we need to let some air out of that balloon.

The songs may represent you because you need to be like the songs you sing — not that you are yet those things.

Yes. You want to be.

And what kind of feeling did you have inside after these violent episodes?

I never liked it. Never. I would worry sick about having to go out on the street, in case a guy I had been in a mill with would come back for more.

And yes I can remember — not so many years ago — we were playing in a local bar here, and some guy threw a glass. And the glass just missed slashing Edge’s arm. And I knew the guy that threw it. There was resentment, because Adam and Edge came from a sort of middle-class background, and people thought, “Oh, U2, they’re not really punks!” But I knew where this guy lived. And he lived in a bigger house than I did. And it took all my energy to stop myself from driving a car through his front door that night.

Were you curious as a kid, but not in an academic way?

I was curious, but I never knew what I wanted to be. One day I’d wake up and want to be a chess player — the best. I’d read a book on it, and at 12 I studied the grandmasters, and I was fascinated. The next day I’d think, “No, I’ll be a painter.” Because I’d always painted, since I was four years old. So I was just wandering. And I’m still wandering. I suppose. But see, I want it all and I want it now [laughs].

You were the first punk in your class — haircut, pants, chain, et cetera. Did you really feel it, or was it just theatre?

It was theatre. I had gotten interested in Patti Smith and then the Sex Pistols. And the great thing about the Ramones was you could play Ramones songs all in three chords — which was all I had then and, in fact, is about all I have now [laughs]. Before that I was interested in Irish folk music. It was around my family. There was a lot of sing-song. And my brother taught me those three chords. He used to play [the Kenny Rogers and the First Edition classic] “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town”. I’m still fascinated by that song.

And my old man was into opera, which, as far as I was concerned was just heavy metal. I like those bawdy opera songs; the king is unfaithful to the queen, then he gets the pox, they have a son, the son grows up and turns into an alligator, and in the end they kill the alligator and make some shoes for the king. But because it’s sung in Italian, people think it’s very aloof. Not at all.

And when the now-famous note went up on the now-famous bulletin board, asking for members to form a band, did you think, “Ah, this is it”?

No. At that stage, I was interested in the theatre. When I was younger, I ran away from home one day to book myself into an acting school. But there was no acting school. My father used to act at a theatre, and I would sit in the front row. When I was 13 or 14, I set up a theatre company in the school I was in, because there was none. I don’t know if I would be a good actor. Now, I’d almost like to write for the stage more than to be on the stage. So when the note went up, I had to be talked into it by a friend.

Was being onstage the lure?

Yeah. And in one of the plays, I sang. I remember the feeling of singing through a microphone and hearing it bounce off the walls. I get a bit of a belt off of that — sort of an electric shock. But even after we started, Adam was the only reason we went any further. He’d say, “I think I know where we can get a gig.” And I’d say, “What’s that?” He’d say, “A place where we can play.” I’d say, “You mean in front of people? But we’re crap.” He’d say, “So are the Sex Pistols.” [Laughs.]

There’d been a precedent for people who couldn’t play.

Yes. You see, the roundabout had just slowed down enough for us to jump on. Any other time, and it wouldn’t have worked out. ’Cause before that it was all the worship of the instrumentalist, and you had to be able to play. All we had was raw power.

The acting fell by the wayside. And I got a job as a petrol-pump attendant so that I could write when the cars weren’t coming in. But then we had the oil crisis, and we had these queues for miles, and the cars just kept coming, so I quit.

Are Edge, Adam and Larry guys you would have chosen for your friends if you didn’t have the music among you?

No. No. Now I would, but not then.

You claim you’re socially inept.

I’m very awkward, I’m not a very good pop star. [At this point, room service knocks. A young attendant brings in six Heinekens, and seeing Bono, he almost drops his tray. He nervously asks for an autograph and is obliged.]

See, your regal presence totally disarmed this poor guy. You seem like a perfect pop star.

Well, I don’t feel like a pop star, and I don’t think I look like one.

What’s a pop star supposed to feel like?

Well, I don’t know. But I imagine if you’re a pop star, that you don’t feel like me. If I was a good pop star, I wouldn’t be telling you about the way I grew up, because I’d want to keep those things from the public. I’d want people to believe I just came out of thin air. Sometimes I wish I were that way. At the moment, actually, I’m going for bastard lessons.

Where do you begin — Refusing Autographs 101?

Like when the twentieth caller knocks on the door to my house, I’m just going to tell them, “Fuck off! Leave me be!” instead of bringing them in for a cup of tea. Which I do, which is just dumb. I think the thing I least like about myself is that I’m reasonable. And being reasonable is a very un-pop-star trait. So I am taking bastard lessons.

In 1979 you said “We’re determined to achieve a position where we have artistic freedom and where we can affect people the way we want to affect them. That position derives from money and success, and we’ll work very hard to get there.” So you did, and now you’re here: pop stars.

It’s true, we did work long and hard to get rid of the anonymity that we now need in order to live. It’s an interesting irony. I can remember thinking back in ’77, “Yeah, we are going to take this all the way.” Do other people think those things? Was it blind faith or just stupidity? And if your dream comes true, is it dangerous to think that all of your dreams will come true?

Well, two tragic things can happen: one is to not get want you want, and the other is to get what you want.

Yeah. But we really haven’t gotten what we want. You see, we live in a culture where the biggest is often equated with the best. And now people say we are the biggest band in the world. So what? That means nothing to me. No, it must mean something. But our want is to be worthy of the position we’ve been put in. To be the best — to make a music that hasn’t been made before. And I don’t know that we’ll get to that point.

Can you assume it’s even possible to get there, playing to crowds of 60,000 people? Aren’t the limitations imposed on communicating to that many people contrary to the notion of experimentation? In this context you become a “product” no matter what your intentions.

Well, live is not the place to experiment. U2 has always been a very different act live than in the studio. Part of rock & roll is about raw power, and that’s what we are about live. In the studio we have experimented, and we will continue to. I suppose what we’re looking for is a better synthesis of the two.

In the studio you usually build from improvisation, and yet when you present the material live, it is very formal, structured, repetitive.

Yes. U2 live is much more like theatre; there is a beginning, a middle and an end. On this last tour, we have been experimenting with that form more than ever.

I must say, there is a real thrill to being onstage in front of 50,000 or 60,000 people. The event is made larger than the group and the audience. It’s an amazing thing to see people united in an agreement, even if only for an hour and a half.

Does it ever frighten you, seeing that?

No, because I never underestimate the intelligence of the U2 audience en masse. I actually feel that they know more about the group than we do.

We were in the audience when the Clash played Dublin. We just got up out of the audience ourselves and played. So I feel very close to the audience. There’s no separation in my own mind. And I know if I told them all to stand on their heads, that they’d tell me where to go.

But you clench your fist in a particular way, and all 60,000 will clench their fists accordingly. Is there not something within this gesture that gives you pause?

When a Japanese man bows to another man, and the other man bows in response, that’s nothing but a sign of consent. When people respond, or when they sing a song I’ve asked them to sing, they are just being part of a bigger theatrical event. The idea that they are rather moronically being lemmings, following Adam, Larry, Edge and Bono off the cliff’s edge with their fists in the air, does not pay them enough respect.

But there is a power inherent in your position, and it would take a certain amount of duplicity or false humility on your part to suggest that there’s not. And that power . . .

Can be taken advantage of. Maybe.

And you never have intellectual or emotional hesitations about that kind of power?

That kind? No. There are other kinds of power — the kinds that are not seen — that worry me. If you could see into the dressing rooms and the offices of a lot of bands in our position, you would see the real abuse of power. Like making a promoter crawl because you are paying his wages; like making the road crew wait for four hours because you are late for a sound check; like the sexual abuse of people who are turned on by your music. I don’t know whether I am guilty of all of those. Maybe I am. But that is the type of power I worry about in rock & roll.

On your tour of the States in 1981, you had, for the first time, people grabbing at you for autographs, and you felt like a commodity and were quite depressed by the whole “gladiators, dinosaur rock” thing, you called it. And then when the group first broke through in the States, a few years back, you said, “I believe in U2 in audiences up to 20,000.” And yet now you are playing to 50, 60, 70 thousand people.

We have to. To do a tour that lasts three years in length would be the end of us as artists. And to do a short tour [playing arenas], where we just ignore people and make them pay scalpers for tickets — I don’t like it. I’ve even said from the stage, “Don’t pay those prices.” But they do. They will pay [us]$100 to see U2, and U2 is not worth [us]$100. So on this tour, we’ve tried to strike a balance of playing indoors and outdoors, so the ones that really want to see us indoors get a chance, and we can play to other people. I think U2 can actually do it. People invented the idea of “stadium acts” — you think of these great chord-crashing dinosaurs. But Stevie Wonder is a stadium act, the Beatles were, Bob Marley was.

Let’s go back to where we started on this, that is, the sort of public power you are able to exercise at the moment. You’ve stated a number of times that the goal of all U2 songs is to make people think for themselves.

To inspire people to do things for themselves. To inspire people to think for themselves. But that’s not why I’m in U2: I’m in U2 because it inspires me . . . I’m here because I couldn’t find work anywhere else. And the real reasons to be in a rock & roll band are probably much closer to ego, and to be onstage and have people look at you and think you’re a great guy. Those are the real reasons — at least when you’re 15 and sing into a microphone. On the way, since that time, we’ve thought about what we’re doing — and we’ve accepted some of the traditions of rock & roll and rejected others.

Let me play the devil’s advocate: it seems like standing among an audience of 60,000, singing the same song, can in no way encourage one to think for oneself.

I disagree. They do think for themselves is my point. But the problem is that in the world we live in, in the West, the doctrine of personal peace and prosperity prevails. If you’ve got a fridge, a car or two, a vacation once a year, you’re OK. And you’ll agree to anything, such as voting for whoever can preserve this. People are subject to a lot of influences that attempt to send them to sleep. There is media. People’s reaction to violence on-screen; the difference between what is real on the news and what is surreal on Miami Vice has become blurred. We are in a big sleep, where I’m OK, you’re OK. And we don’t ask questions that have difficult answers.

And if U2 is throwing cold water over that kind of thinking and people are waking up — that’s fine. But that’s not the reason we’re there. We’re there because this is the way we feel about the world. Now people have to choose; they go to the supermarket and choose what brand of cornflakes to buy and what detergent. They have to make choices. And U2 is just one choice.

Isn’t there a worry for any serious artist that he represents just such a choice — that he is packaged and sold like a detergent, that he is advertised and marketed in a certain way, that he is a commodity?

From my point of view, it’s just important that we’re there, that people have a choice. We are getting to the point where the choices are being dictated for us — records are being banned and choices limited. Rock & roll in the ’70s was just completely banal. I don’t want to put U2 up as the alternative, but I think it is a good thing that a song like “With or Without You” was played on Top 40 radio.

Why?

Because I think it is provocative, both sonically and in what it suggests. When I was growing up and listening to the radio, I would hear maybe one song in every 20 or 40 and 50 that I would like, that I would feel was an alternative to the music that other people deemed fit to hear on the radio. That’s why I feel it’s important that U2 is on the radio, that we don’t leave the radio just to those product-oriented people. Because there are groups, just as there are record companies, who treat music like a tin of beans — a product to be sold.

And yet U2 is a product . . .

I don’t think of it that way.

But the record company may, and the management company must, and the advertisers do, and the promoters do, and the radio programmers do, and the T-shirt and poster manufacturers do . . .

And that is why rock & roll is in the situation if finds itself in in 1987. Because no longer do fans of music run the music business. Fans of money run the music business.

Without being too precious about U2, let me say I’m learning to accept T-shirts, what I’m not willing to accept is bad T-shirts. There are traditions in rock & roll I am accepting, but what’s important to me is the music. It would be a trap for me to spend my whole life fighting a battle about something — my knuckles would be bleeding from beating on the walls of the music business — when really what my fingers should be wrapped around are the frets of a guitar, trying to write down the way I feel and make it a song.

In some way, intellectually, it’s almost a defeat to be where you are.

Yes. Talk to Miles Davis about it.

Does this thing ever give you the blues?

Yeah. What gives me the blues more than anything is the glass case that comes with success in rock & roll. The one area of control, real control, that we have is the music, and so everything must gather around that. And our organisation is set up to protect that. And in order to do that, you take on some of the excess baggage of rock & roll — like a plane — so that you can get home after a show and see your family and your friends who you haven’t seen in five years. And if your motive is to protect that music, then as far as I’m concerned, those things are OK.

Let’s go back to the glass case.

The glass cage, it could be called.

Now, a lot of it has to do with money, and because of who you are — what your values are — you’re resistant to even deal with it.

Listen, I felt like a rich man even when I had no money. I would live off my girlfriend’s pocket money or the people on the street. Money has never had anything to do with how rich I feel. But it is almost vile for me to say that money doesn’t mean anything to me, because it means a lot to many people. It means a lot if you don’t have it.

But how do you deal with the fact that you do have it? You’ve said in the past, “I just don’t want to see it”, which sounds like the first stage of reacting to anything that’s traumatic, and that’s denial.

Yeah [pauses]. Oh, boy. All money’s done is remove me from my friends and family, which are my lifeblood. It has cut me off. People have said, “You’ve changed”. But sometimes it’s not you who has changed but the other people in their reaction to you. Because they are worrying about the price of a round of drinks, and you’re not. It’s the butt end of stardom. And this fits in perfectly with the U2 sour-puss image — you know, U2 is number one, and they’re too stupid to enjoy it [laughs].

Well, as W.C. Field said, “Start off every day with a smile, and get it over with.” Maybe you’re the W.C. Fields of rock.

[Laughs, almost defensively] Well, I do enjoy the jet so I can get home while on tour, and I do enjoy hearing the record on the radio, so I don’t want to come across as being down-in-the-mouth about being Number One. I am on top of the world, it’s just that something else is on top of me.

Your great couplet from “New Year’s Day” doesn’t only apply on a macro level to society but on a micro level to the band: “And so we are told this is the golden age/And gold is the reason for the wars we wage.”

Yeah, and I’m starting to see the value of being irresponsible. You know, you read about the excesses of the rock & roll stars of the ’70s — driving Rolls-Royces into swimming pools. Well, that’s better than polishing them, which is the sort of yuppie pop-star ethic we’ve got in the ’80s [Laughs].

Brian Eno says something interesting about money. He says that possessions are a way of converting money into trouble. You can almost trace the downfall of some of the great rock & roll bands by the rise of their consumerism. They were consumed by it. You can see that when they got fat and settled down, their music wasn’t the same. And I don’t want that to happen in U2, ’cause it’s the music that is the centre of our world — and I don’t want that to be replaced by either, one, material wealth, or two, the worry about it.

It’s said that there’s never a true artist who couldn’t handle failure, but that many have run aground on the rocks of success.

I suppose I just don’t see U2 as a success. I just see U2 as a whole list of failures: the songs we haven’t written and the concerts we haven’t played. I don’t know if we will make it through. I suppose the chances are that we won’t. But maybe if we know that, we will.

What could stop you? The fact that you and Edge are the focus musically, and you are the leader lyrically?

It’s true that the two of us are becoming more interested in the craft of songwriting, as opposed to the band’s overall interest in improvising. But I think we’ve gotten it right in the past — there are four of us, and we are committed to that. What would a U2 song be without Larry playing the drums? “Pride” started with Larry and Adam. Adam just about wrote the backing for that.

Do you feel limited being in U2?

Well, if you want to be in a band, I think U2 is the best band to be in. But sometimes you become restless. You think, “Wouldn’t it be interesting to write a play or a book or to work with Miles Davis?” Sure. But to be in a band is an amazing feeling, both in its fraternity and fun and frolics, as well as its musical achievement. See, only about 10 people in the world make me really laugh, and four of them are in the band — including Paul [McGuinness], our manager.

Before “The Joshua Tree”, you had an album in your head you said U2 almost couldn’t play. Did you put a lot on the shelf in making “The Joshua Tree”?

We did about 30 songs, so there’s a lot in gestation. There’s a few records we still want to make, and maybe some of these songs will be completed.

Rock & roll, it seems, is caught up in juvenilia. Relationships are at the level of sex in the back seat of a Chevrolet. Now I’m interested in what happens further down the road — the violence of love, ownership, obsession, possession, all these things. And I think rock & roll is wide-open for a writer who can take it all down. And take it to the radio. “With or Without You” is a really twisted love song, and it’s on the radio.

Let’s go back a few years. During the War tour, you said that you thought rock & roll was full of shit, and that you were fed up with it.

And the question is: Do I still think rock & roll is full of shit? Yes, I do. It was full of shit then, and it’s still full of shit, and it’s always been full of shit. For me, rock & roll has always been as black as a mine — but you could find a jewel down there that made it all worthwhile. At the time, we just didn’t seem to fit in. I had to ask myself, “What is it about? Elvis Presley shooting at the television while reading his Bible; Jerry Lee Lewis believing in God and playing the devil’s music with his 14-year-old bride at his side; John Lennon at the peak of his success singing ‘Help’. Rock & roll is almost about the contradictions — my own desire to do something relevant with my life, as well as my own enjoyment of driving down Park Avenue in a limousine.

I guess I’ve just accepted the contradiction: being in a privileged position and writing about those without privilege; being in a position of having and writing about those that have not; being fully employed and writing a song about unemployment. These are contradictions, and they’re awkward at times.

Do you feel lonely?

More and more, over the last years I feel cut off. I used to go out the back of the venues, and there would be some people hanging around, and we’d chat, maybe sign some bits of paper and go back to their places and sleep on the floor, talk through the night. Or I’d have people come to my room. One time I had 13 people sleeping in my room, on the floor. Now I go out, and I don’t know who I can talk to. I’ve got people who want to kill me, people who want to make love with me, so they can sell their story to the newspapers, people who want to hate you or love you or take a bit of you. So you end up going back to the hotel and back to your room, and even if it’s a suite in the finest hotel, after being on stage in front of 10,000 or 100,000 people, it’s almost a prison cell. But, hey, if you can’t stand the heat in the kitchen, then get out.

But I have fewer friends now than I did five years ago. I know more people. I’m a lot of people’s best friend.

Has this made you cynical?

No, I don’t want to be cynical. Maybe lesson number two in How to Become a Bastard will teach me to be cynical [laughs]. I’m open.

The challenge of your position is, How do you make it not a prison?

Imagine what it would be like being a solo performer. At least we’ve got each other. We’re a band, a real band. I can always drag Edge out of bed and talk.

I hardly saw Ali, my wife, for a year. Nineteen eighty-six was an incredibly bad year for me. It’s almost impossible to be married and be in a band on the road — but Ali is able to make it work. Then you tell the press that she is her own person and very smart and not some dolly girl and that she doesn’t take any shit from me, and they read into it a marital breakdown. And I think, “Well, what sort of women are they married to?”

Have you thought about having children?

I’m both frightened and excited by it. I feel just too irresponsible. The kid would end up being my father. I’m the sort of guy where the son is sent out to fetch his dad and bring him home. But I think Ali would be an amazing mother, and it might be exciting to see new life. I’d just be afraid that if it were a boy, it would turn out like me.

Is Greg Carroll’s death the most significant thing that’s happened to you in the last few years?

Yes, yes it is. It was a devastating blow. He was doing me a favour, he was taking my bike home. [Carroll, a U2 employee, died in July 1986, at the age of 26, in a motorcycle accident.] Greg used to look after Ali. They would go out dancing together. He was a best friend. I’ve already had it once, with my mother, and now I’ve had it twice. The worst part was the fear, and fear is the opposite of faith. After that, when the phone rang, my heart stopped every time. Now when I go away I wonder, “Will these people be here when I get back?” You start thinking in those terms. We’ve never performed “One Tree Hill” [a song about Carroll’s funeral]. And I can’t. In fact I haven’t even heard the song, though I’ve listened to it a hundred times. I’ve cut myself off from it completely. I want to start singing it soon.

How much of “The Joshua Tree” was written after Greg died?

I don’t know.

Because it clearly stands above your other records in its openness, its willingness to reveal and not conceal.

I agree with you. I think so. It’s a very personal record. Greg’s death brought us together in a way. That’s what always happens. It becomes the family again.

So much of fashionable pop has been presented with coolness, distance.

It was sad for us in U2 to discover when we were 18 that the Sex Pistols were a “good idea” that someone had thought up. Because when we were 16 we had believed in it, we believed in rock & roll. Often it is a sham. And it can be entertaining or even enlightening as that, but that’s not what I like. I like it to be loose, to laugh at itself. Tutti-frutti, yes, but being manipulated by an artist, no.

There have been times when your work has not been so revealing. I think one reason some folks had problems with “The Unforgettable Fire” is because some of it seemed not ambiguous but confused, and confusion is irritating, such as on “Elvis Presley and America”.

There is confusion in that. That is genuinely confused. But we were not at all confused in making the decision to put it there. A jazzman could understand that piece. He would just listen to it. Was it self-indulgent? Yes. But why not? The Unforgettable Fire was a beautifully out-of-focus record, blurred like an impressionist painting, very unlike a billboard or an advertising slogan. These days we are being fed a very airbrushed, advertising-man’s way of seeing the world. In the cinema, I find myself reacting against the perfect cinematography and the beautiful art direction — it’s all too beautiful, too much like an ad. And all the videos have the same beauty and the beautiful shadows and . . .

Your videos, too!

Yeah. And if I had made a film a few weeks ago, it might look like that. But something is happening in me that makes me want to find a messier, less-perfect beauty. I’d like to see things more raw.

Is it harder to please yourself now? Are you tougher on the lyrics?

I used to see the words as music and my voice as an instrument. It was the sound of the words as much as the sense that interested me. The way they bumped against each other, not necessarily their meaning. The idea of a couplet I think I discovered about two years ago, talking with Elvis Costello. But my writing at best is still sort of subconscious. “Running to Stand Still” is pretty much as I wrote it the first time, as a sort of prose poem.

You take a stance against cliché, and yet there are clichéd images throughout “The Joshua Tree”. Through the storm we reach the shore, mountains crumble, rivers run to the sea.

Yes. I was rooting around for a sense of the traditional then trying to twist it a bit. That’s the idea of “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”.

But there are other places where clichés are used without the sense of irony they have in that song, and they just come across as stock images or metaphors, whereas a few albums ago, before you had developed as a lyricist, they wouldn’t have been noticed.

Umm. There are two rival instincts in me as a word writer. One is an interest in writing subconsciously, almost in a half-sleep, which is the way I wrote “One Tree Hill”. And the other instinct is a desire not to be self-indulgent and not to use clichés the way rock & roll music has always used them. The Beatles were experts at it, every single song: “Please Please Me”, “The Long and Winding Road”.

Do you think it’s more important to be good or to be original?

I think it is more important to be good. But rock & roll is at its most exciting when it’s pushing at the parameters a bit. When it stands still for too long, it gets stagnant.

Have you ever felt dry? Like you were operating in a closed loop of your own devices and had nothing new to say or a way to say it?

No. When I was at school, I remember we were talking about William Butler Yeats and the different periods in his life. And the teacher told us about a period when he felt he had nothing left to say, and how this often happens to poets. I said, “Yeah, but why didn’t he write about the fact that he had nothing left to say?” And that is what I have always done — started with what I feel. As it says in the Bible, know the truth, and the truth will set you free.

You’re never frustrated with your own limitations?

I’m so undisciplined and untidy, and the everyday doings of my life are such a mess, that I get frustrated. I write on the bus, on the backs of cigarette packets or on the table mats in restaurants and lose them. I lost a song I wrote with Bob Dylan, in the early-morning hours after a gig in L.A., during our last tour. I’ve got to own up to being a writer and just write. So now I’m trying to develop the craft of songwriting, so that what I do neither dries up nor blows up in my face. And all of us are committed to thrashing about in the studio.

Do you think you’ve gotten past shouting now — and are finally a singer?

I’m becoming a singer, I think. I’m not a soul singer yet, but I think I’ve got soul. We may not be accomplished musicians, we are raw, but I think all I want is the soul. Because, now, as we listen to Coltrane, if that didn’t have soul, I wouldn’t listen to it. I’m not impressed by the jazzman’s technical ability, but rather I’m impressed by the way he can use his skill to tell a story, to create a mood, to make me believe. That’s the ability to reveal and not conceal, and that’s what I want.

You have been insisting in interviews all through this tour that you take the music seriously, but not yourself. It’s almost defensive, as if in this age it’s not cool to take yourself too seriously. Why the dichotomy?

It’s just that we have this image of po-faced young men. Severe and serious. Like the album covers. I mean, are these guys too stupid to enjoy their success? Don’t these guys ever go down to the pub or take the piss out of each other? Of course we do. There is a somewhat unbalanced impression of U2, and that’s where that comment comes from.

It’s my suspicion that you do take yourself rather seriously. What’s wrong with that? This is the age of Lite beer and lite music and lite politics, so why be defensive about being heavy?

I have to be careful that people don’t manipulate our public image into something we’re not. When we come off stage, we’re just four guys in the dressing room. I think it’s OK to be serious as long as you’re not boring.

Well, if you don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn.

Is that a jazz phrase? I understand it. See, I’m a guy with no mid-range. I’m all bottom and all top, emotionally. I let people take advantage of me way past the point others let people go. But when I break, I really break. Watch out.

So your “reasonableness” is a defence against losing it?

Yeah, and I’m sick of it. It leads me to make a lot of bad decisions. I just wish I could be a little more testy or say, “Stop”, to someone who is doing something I don’t like. I put up with it. There are some hilarious examples of this. When I first got married, I put up with an alcoholic house painter for two weeks, who painted rooms in the colours he wanted — but then he painted the front door silver. I told him, “I don’t like silver.” He said, “Everybody is going for the chrome-door look.” At which point I took him and all his paints and threw them out of the house.

Do you weary of the missionary vibe that has come to surround you — that you are some sort of saviour for Irish youth, or some kind of quasi-political, quasi-religious figure to your fans in the States? How do you deal with this?

[Long pause] Oh, boy. I don’t have an answer to that. But I know that I have to find the answer. On one level, it’s exciting. Amnesty International doubled its membership because of that tour. But it’s not so exciting having a psychopath call you up day after day because he thinks you’re left-wing politically. Writing a song is one thing, but a song can’t save anybody’s life.

You’re talking about the differences between art and action. Can you imagine a time or a condition where you would feel the need to put down the guitar and pick up a gun?

You mean, is there a point where instead of singing about apartheid you should be on the street demonstrating? Should you be tying yourself to the gates of the South African embassy? I don’t think an artist has that responsibility; his responsibility is to his art, ultimately.

Don’t you feel an artist’s responsibility, above and beyond his art, is ultimately to his fellow human being?

I need a few cornflakes before I answer that. [Eats out of the box] No greater love has a man than he shall lay down his life for his friends. Who said that?

“You can get much farther with a kind word and a gun than you can with a kind word alone.” Who said that?

[Laughs] It wasn’t Jesus.

It was Al Capone. Come on, Bono, let’s say you were around in the ’40s instead of the ’80s. It’s one thing to write songs about how the Third Reich is in general a bad idea, and it’s another thing to fight it. What would you have done?

You have to give me a few weeks before I can answer that.

Is it all war you oppose, or is there anything that you would fight for?

For instance, would I defend my home and my country? Would I defend my family with violence? [Pauses] Two guys once walked by the door of a beach house where I was staying. They were wearing green berets and carrying rifles. They just came down the driveway. They did not look like policemen. It was just after “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, so I didn’t know what was happening. And before I got a chance to think about it, I had a large knife in my hands that I took from the kitchen. And that sickened me, because I felt like a hypocrite. But that was natural instinct. That’s all I can tell you. That’s about as far as I’ve gotten on this one. This is a very interesting question, and I don’t have an answer for it.

OK, let’s broach the frequently covered but still murky subject of your relationships to religion and spirituality.

Well, religion has torn this country apart. I have no time for it, and I never felt a part of it. I am a Christian, but at times I feel very removed from Christianity. The Jesus Christ that I believe in was the man who turned over the tables in the temple and threw the money-changes out — substitute TV evangelists if you like. There is a radical side to Christianity that I am attracted to. And I think without a commitment to social justice, it is empty. Are they putting money into AIDS research? Are they investing in hospitals so the lame can walk? So the blind can see? Is there a commitment to the poorly fed? Why are people left on the side of the road in the United States? Why, in the West, do we spend so much money on extending the arms race instead of wiping out malaria, which could be eradicated given 10 minutes’ worth of the world’s arms budget? To me, we are living in the most un-Christian times. When I see these racketeers, the snake-oil salesmen on these right-wing television stations, asking for not your [us]$20 or your [us]$50 but your [us]$100 in the name of Jesus Christ, I just want to throw up.

And your religious background and education in Ireland?

In Ireland we get just enough religion to inoculate us against it. They force-feed you religion to the point where you throw it up. It’s power. It’s about control: birth control, control over marriage. This has nothing to do with liberation.

And what’s a Christian to do about liberation? Social action?

Well, I am not sitting here with flowers in my hair, chanting away. I do have responsibilities, and actions speak louder then words. That’s why I don’t feel guilty about the money we’ve made. I sometimes feel embarrassed, but not guilty. I am in a situation where the actions sometimes do not equal the words, and I would like them to. Charity is a very private thing.

What about liberation theology, which promotes social action on behalf of the poor?

I think the danger of liberation theology is that it can become a very material ethic, too material. But I am really inspired by it. I was in the Church of St. Mary of the Angels, where liberation theology has a base, in Nicaragua. I did not like the romanticisation of the revolution that I found there. Because I think there is no glory in dying a bloody death. I attended a mass, and the priest asked all those who had lost a loved one for the revolution, fighting the contras or whatever, to stand and come forward and call out the name of your loved one.And all these people stood, and called the names one by one, including sons and daughters. And with each name the congregation would cry, “Presente!” — meaning they are present. It was amazing to see such solidarity. If you are not committed to the poor, what is religion? It’s a black hole.

Let’s get more mundane here. Where are you going next — film, theatre, other music, writing?

The most exciting of all those possibilities is to see where U2 can go. I’d like to see if I can stretch U2 to take words that I am hearing. I’m really excited about being in the band, and in fact, this is the first time all four of us have been excited about being in the band at the same time. The key for us as a band is to reinvent ourselves.

Despite your interest in the band, are there other things you’re interested in pursuing?

The fact is, there are very few things I am not interested in. I am a very curious man.

I am writing a play with one of my best friends, Gavin Friday, who is a performance-artist-singer-writer. We’re writing a play called Melt Head. I’m interested in theatre, in Irish theatre and Brechtian theatre and Kurt Weill’s music.

I’ve a whole pile of writing I may one day publish, just bits and pieces. I also painted during The Joshua Tree. A friend and I are having a show together in a Dublin gallery. But instead of paintings, I am going to show some photos I took the last week I was in Ethiopia — because I want to keep the awareness of that alive.

There is also a project I am interested in writing or co-writing with Edge, which would be like a play to be filmed. As far as acting, I’ve turned down a few roles. I find it hard to look at myself on the television, much less a big screen, and yet, if the right role turned up, I’d take it. I’m interested in the mentality of violence; terrorism interests me. Because it’s the everyday Holocaust of our times. The idea that two IRA men were blown up because they stood too close to the bomb they had set — because they wanted to see the carnage — is beyond my understanding, and I’m fascinated by it. Terrorists are ordinary men who have either ability to take the lives of other ordinary men because of the way they see the world. I am talking about the ability to knock at the door of a man’s house in Belfast, and when he answers the door, to shoot him 10 times in the head in front of his children. This is something that I would like to understand. I think I could play the part of a terrorist.

Are you ever at peace with yourself?

I’m happy to be unhappy. I’ll always be a bit restless, I suppose. I still haven’t found what I’m looking for [laughs]. Let’s go for a ride in the car, OK?