At this point in the progress of Gerhard Richter’s public career, it seems appropriate to turn down the heat a bit and try, for once, to approach Richter’s paintings as quietly and carefully as he approaches making them. There is justification for doing this. Richter himself has always insisted that his practice of painting is grounded in the civilized prerogatives of freedom and doubt, modesty and hope, and our knee-jerk response to his insistence has usually been to assuage his doubts and contravene his modesty, to reassure the artist of his own importance. Either that or we purport to take him at his word while theatricalizing the terms of his practice. We exacerbate “freedom and doubt” into “license and despair”; we transmogrify “modesty and hope” into “bourgeois self-loathing and progressive historical certainty”—thus making of Richter an altogether different kind of artist—a radical connoisseur of bad faith, if you will.

The terms Richter has offered us for his painting practice, however, as he states them and as they stand, have real consequences. Freedom, in Richter’s idiom, is as inextricable from doubt as modesty is from hope. The freedom he grants himself to paint any kind of picture he wishes, in any manner he might choose, derives absolutely from his perpetual and oft-articulated doubts about whether he is doing the right thing in his paintings, and whether painting itself is the right thing to do. Freedom is choice, in other words, and to doubt is to face an endless parade of choices, fully aware that one is probably inadequate to the task of choosing. To choose, then, and then to choose again is a manifestation of hope. Certainty, on the other hand, has already chosen. It has divided the world and stopped its tumultuous procession. As such it is a form of violence. As an artist, to have a “style” that betrays an agenda is to have chosen. By extension, style is violence.

Richter’s position, then, is that painting is a serious activity whose possibilities are decimated when we descend into certainty or seek certainty from artists, who, after all, only look and choose in the present moment. When Richter talks about himself as an artist, he invariably portrays himself as one of his own beholders. He is always looking for something or waiting for something to appear, and, when it appears, he decides, knowing that tomorrow he must decide again. This explains Richter’s tendency to discount the relevance of his own skills and intellectual abilities when assessing his importance as an artist, because, in Richter’s aesthetic, these attributes come into play well before the fact. Art’s value does not derive from the quality of the artist’s manifest intentions but from the authority of contemporary judgment that validates its reception—a process that begins with the artist’s choice and ends with the public’s. In this sense, Richter is a true pop artist, presuming that his paintings, like Jasper Johns’ flags, derive their authority not from the artist who made them, but from the citizens who salute them.

Richter’s hope, then, is for his beholders (and for himself as one of his own beholders), for their sensitivity and judgment, for their flexibility and tolerance. So, although we are under no obligation to take any artist on his own terms, it might be interesting, on the occasion of this book about a discrete group of Richter’s paintings, to address them in the sense that Richter proposes them—as contingent, tentative products of a painter’s daily practice offered up into the fluid, tenebrous realm of perceptual adjudication. The group of paintings in question is comprised of eight, modestly scaled oil paintings that were painted more or less simultaneously during the summer of 1999 and then arranged, after the fact, into a sequence numbered 1 through 8. Each of these pictures is painted in a “television” palette dominated by red, green and blue and executed in Richter’s late abstract manner.

As Richter describes this process, each picture is

then it is a Something which I understand in the same way it confronts me, as both incomprehensible and self-sufficient. An attempt to jump over my own shadow….

The pictures in 858, subjected to this process, have been brought to different levels of articulation. Some have been declared “finished” earlier than others and consequently feel “younger” than their fellows. All the pictures share a common language, however, and this staging introduces a network of familial and temporal relations that Richter exploits in his sequential arrangement.

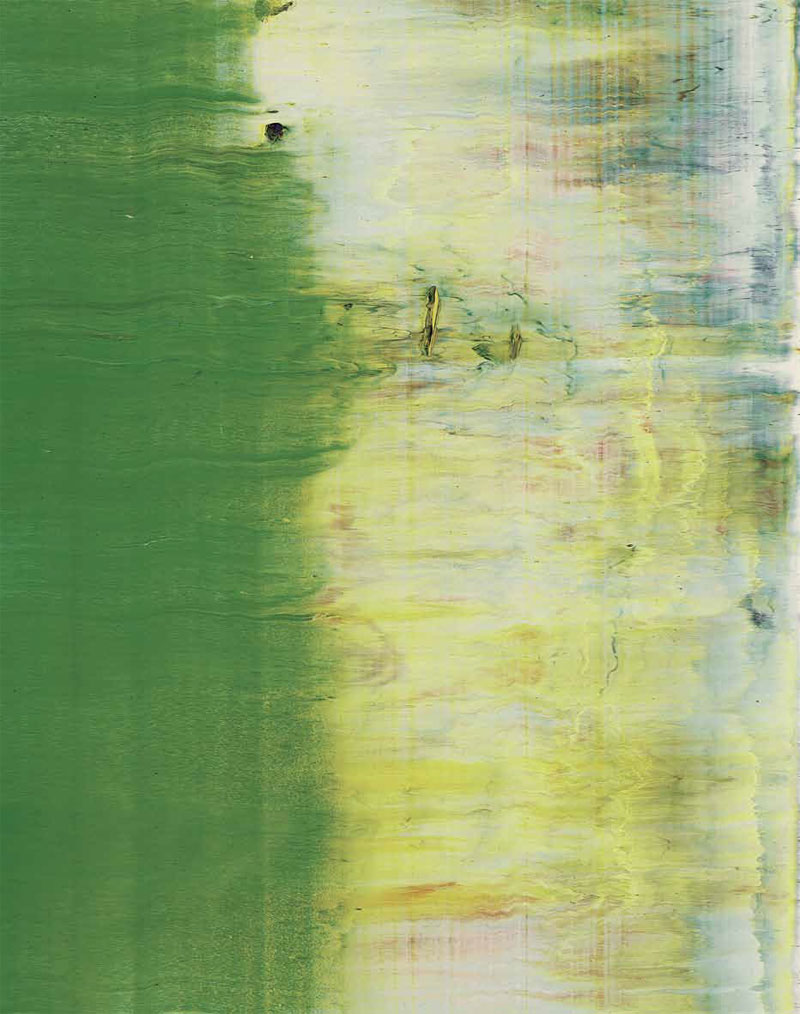

Geological layers of paint have been applied to the surfaces of these pictures with a squeegee in continuous gestures across the support. The gestures are predominantly, although not exclusively, horizontal and vertical, varying in their relative wetness, thickness and cover. Half of the pictures in 858 are scarred by gestural marks that simultaneously add color and wipe other color away. In the “oldest,” or most evolved painting in the sequence (Number 6), these marks have highly articulated widths and shapes. They present themselves as figures against the blurred ground of dragged paint. These elements—the palette in its weighted variations, the drag in its different directions with its variable attributes, the scarred marks of various widths and lengths—constitute the language of the paintings as utterances. Their variations and repetitions define the pictures individually and articulate their musicality in sequence.

The formal acuity and arrangement of 858 as a musical sequence of abstract paintings, however, is considerably complicated by the aura of representational inference that is created by Richter’s technique of dragging paint. Because of this technique, the paintings always seem to be on the verge of showing us something, and the sources of this haunting inference derive, interestingly enough, from the birthday of modern painting—the historical moment when painting and photography diverged as practices. First, of course, Richter’s dragged gesture across the surface approximates in reverse the blur created in photographs when the camera or the subject moves and the aperture is open. Second, the tiny oval and fractal spaces caused by the irregularity of the squeegee’s traverse literally recreate (and once again in reverse) the scatter of marks that, in Impressionist painting, generate the illusion of liquidity. The combination of these two historically resonant visual effects may be taken as a classic instance of Richter’s effort to keep “the most disparate and mutually contradictory elements, alive and viable, in the greatest possible freedom.”

In doing this, Richter transforms the secret vice of abstract painting into a complicating virtue. As we know, abstract paintings can never not be read as pictures and this vice is without remedy. In the same way that poems are not so much historical utterances as ahistorical imitations of historical utterances, paintings are less historical visual occasions than ahistorical imitations of historical visual occasions. Thus both poetry and painting, as irrevocably mimetic practices, are always presumed meaningful (which is to say referential) by their very nature. Moreover, in the tradition of western art, the responsibility for divining the meaning of mimetic expressions falls not on their originators but on their receptors, whose primal mandate is to respond by finding meaning. In this tradition, all images are presumed mimetic and burdened with the presumption of visual reference, so, whether or not subjects are put there, they will be found to be there.

Acknowledging this presumption, Richter’s paintings in 858 allude to photography while mimicking the representational devices of Impressionist painting. In the classic pop manner, they portray not Things-inthe-World but Ways-of-Portraying-Things-in-the-World. This creates a situation in which the pictures are invested with an aura of pictoriality without actually depicting anything—in which red, green and blue allude to representations of fire, field, water and sky (which they can’t not do) without actually representing any of them. Afloat in this aura of reference, painterly traces of the artist-in-action are deftly transformed into fugitive allusions to the world-in-action, and both are effectively occluded. Richter’s gestures reference the artist without expressing anything, reference the world without depicting anything, and, in doing so, the pictures maintain themselves, as Ellsworth Kelly’s do, at the exact interface of the world and our knowing of it, alluding to both, bound to neither.

Under these conditions, the unstable pictorial ambience of 858 is so pervasive that, even though we hear the music of its formal arrangement, we are never encouraged to listen to it. Almost certainly, Richter’s decision is to rely on the acuity of what we see, whether we are looking at it or not, although if we do look, we immediately recognize the patterns. The paintings in 858 are arranged into a primary set of seven-and-one, a musical subset of four-and-four, and a base sequence of two-two-twoand- two that has musical, dramatic and poetic overtones. The primary organization of the sequence into seven horizontal aluminum paintings and one squarish painting on linen can be read easily enough as seven aluminum “words” followed by a terminal linen “punctuation,” the shift in support alluding to the shifted nature of the terminal sign. The sequence of paintings, as paintings, however, is also readable as a traditional eightbar musical cadence concluding with a single whole note.

In either case, the traditional musical set of eight with an irrational element in the eighth position insists on some sort of formal closure, and this sense of closure is reinforced by Richter’s positioning of similarly “young,” liquid, and predominately green paintings (858-1 and 858-5) in the one and five positions. This repetition divides the sequence into two four-bar expressions, and, recognizing this four-by-four musical structure, we look for the classic division of Western musical sequences into statement-restatement-release-return, and find a visual version of it. First, Richter has positioned the paintings in iambic groups of two. The “younger,” less articulated paintings occur in the odd-numbered positions as unstressed syllables—the youngest and least stressed pictures occurring at the one and five position, while the unstressed paintings in the three and seven position are slightly more articulated.

The “older,” more densely articulated paintings occur in the even-numbered positions as stressed syllables, occurring in an arc of escalating complexity from 858-2 to 858-4 to 858-6, which occupies the pivotal position. This painting, the most articulate and complex of the sequence, is located at the apogee of the temporal arc. It includes the full language of the series: (1) the squeegee drag, which in this stressed instance moves irregularly and on the diagonal; (2) the full palette of the series, now including yellow, which is otherwise deprioritized; and (3) the scarred marks, which in this instance take on shape and force against the ground of the drag. All of these features, occurring in a painting located in this position, mark 858-6 as the musical release of the temporal expression. In a sonnet, this would be the volta, or the “turning.”

If we translate this sequence into the equally appropriate dramatic terminology of introduction-complication-climax-and-resolution, 858-6 functions as the climax of the pictorial narrative. Whether we call it a release, a volta or a climax, however, the theatricality of this pivotal picture is exacerbated by its position immediately following the quick diminuendo of 858-5, which is the least stressed yet swiftest image in the series, and immediately preceding 858-7, an unstressed image in which the scarred marks that occur in the initial painting recur in a rhyming configuration, signifying a movement toward closure. Finally, as befits its terminal position, the configuration of 858-8, although highly complex, is much less dramatically non-uniform than the climactic 858-6. This final painting, more inclusive, absorptive and entropic than its predecessors, gathers the full language of all these paintings into a final, softened, dissolve and fade.

This is the structure of 858 as seen in sequence, and if there is any general observation to be derived from it about the nature of Gerhard Richter’s art, it is simply this: Richter abjures division, and, if 858 “works” as seen, he is right to do so. His efficacious appropriation of artistic, poetic, musical and dramatic devices for 858 demonstrates the undivided unity of art as a cultural category of response, as does his polygeneric practice of painting un-styled landscapes, still lifes, portraits and abstractions. Both of these endeavors rest on the assumption that, as beholders of art, we may experience different things—pictures, paintings,poems, sonatas, tragedies—but our experiences of these different things are not different kinds of experience. Rather, they are varieties of the same experience, intricately connected by analogous attributes and grounded in the tradition of performance and response.

When Richter insists on the profound connection between his art and traditional art, then, he means something quite specific. He is arguing, as he always does, for painting as a daily practice, and daily practitioners do one thing, whether they are practicing art, law, medicine, or basketball: they internalize a vast repository of historical precedents out of which they fashion idiosyncratic responses to the novelty of the present. In doing so, they aspire to make new art, new law, new therapies and new moves to the hoop, but only in art is “newness” required for the work to achieve a state of visibility, and then required again in response to the perpetual novelty of the next morning. The resources of the past are indispensable to the demands of such a practice, and certainty is the death of it, because only in art is the practitioner his or her own client—the artist’s own primary, critical beholder—and working in this double role, one can never plan or strategize or even think; one can only act and look and hope.

own right, pictures that are about a possibility of

social coexistence. Looked at in this way, all that

I’m trying to do in each picture is to bring together

the most disparate and mutually contradictory

elements, alive and viable, in the greatest possible

freedom. No Paradises.

—Gerhard Richter