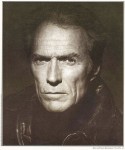

Clint Eastwood

CLINT EASTWOOD

CLINT EASTWOODRolling Stone

September 17, 1992

The brief for this and seven other interviews with film directors (Francis Ford Coppola, David Lynch, Oliver Stone, Spike Lee, David Cronenberg, Robert Altman and Tim Burton), conducted over a two-year period between September 1990 and September 1992, was to identify directors "who work within--and perhaps push against--the bounds of commercial narrative cinema, and who each have produced a substantial body of distinct work: directors who might be thought of as auteurs within the system loosely conceived as 'Hollywood.' " To entice each director to sit for the interview--in the typical transactional mode of both commercial journalism and commercial film--each magazine piece was always pegged to the release of the director's next movie. But I viewed the formula as a necessary inconvenience, and pursued a broader and deeper dialogue wherever possible.

Fuller, more complete versions of the first seven of these interviews were published by Faber & Faber in 1992 as Inner Views: Filmmakers in Conversation. The eighth interview, with Clint Eastwood (below), was conducted too late for inclusion, but was collected in the later, expanded version of the book, under the same title, which Da Capo Press published in 1997.

At Euro Disney, outside Paris, four high-profile architects have built five hotels celebrating various aspects of the American landscape: the Hotel New York, the Sequoia Lodge, the Cheyenne, the Newport Bay Club and the Hotel Santa Fe. This last inn, a Southwestern tongue-in-chic extravaganza, is punctuated with rusting vintage cars, a saguaro cactus in a glass cage and a parking lot that evokes a drive-in movie theater — the guests have to walk under the screen to enter the hotel. The architect, Antoine Predock, wanted to leave this giant movie screen provocatively blank. (The Europeans would simply raid their memories for images to project.) But Disney said no. A blank screen would not do. Well, then what do you paint permanently onto a movie screen outside Paris to conjure the myth of the West? Clint Eastwood — of course. “There is no one more American than he” is what Norman Mailer said, hitting the nail on the hard head, steely gaze, tight jaw. There is always a bullet in his gun, pain in his heart and a cold gray rain of rage in his eyes. For years the biggest international movie star on the planet — turf that he ceded in the last half of the Eighties to actors with bigger biceps (in Hollywood) and bigger guns (in Washington) — Eastwood has metamorphosed not into the dusty legend we might expect but rather into an ambitious filmmaker. In 1988, Bird, his downwardly spiraling riff on Charlie Parker, was avant-garde in its methods and its madness and, while saluted by the critics, left most of the audience behind. In 1990, Eastwood stretched again with White Hunter, Black Heart, a comic take on John Huston’s whimsical, obsessive attempt to shoot an elephant before he’d shoot The African Queen. Without question, in these last twenty years, Eastwood has ridden a long way from his first film as a director, Play Misty for Me.

And now Eastwood, who first came to prominence in a trilogy of westerns for Sergio Leone, has added to the lore with Unforgiven, his sixteenth feature as director and thirty-sixth as star. High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) and Pale Rider (1985) are Eastwood’s grand triptych of westerns; Unforgiven is the frame that changes how we view them. A polished piece of rawhide revisionism, it’s antiromantic, antiheroic and antiviolent. It’s Eastwood’s first dance with myth where the music’s not cartoonish: It’s mature, and now, at sixty-two, so is he. If Unforgiven is not his last western, it should be; if it’s not recognized right away as a classic, it will be.

I met Eastwood at Mission Ranch, a hotel he owns near his home in Carmel, California. Cordial but distant at first, he was quite friendly by the end of the night, though he keeps self-analysis a stranger in town.

What’s the most vital thing to you about the work you do?

At this point in my career, it’s the constant reaching, the constant stretching for new ideas or even, in the current project, variations on a theme. It’s very hard to find things that haven’t been done. But I’m always looking for that excitement. Sometimes it doesn’t happen.

Is it an emotional satisfaction or on intellectual one?

I like to respond to movies — as a member of the audience — on an emotional level. I don’t always: Sometimes I find myself getting carried away with how it’s done, and that’s a sign usually that it wasn’t done so well. It’s an emotional thing: Would I like to see this? Would I like to be in it? Would I like to direct it? I ask myself a lot of questions, but I usually don’t spend a long time answering them. I usually make a decision rather fast.

On intuition?

Sometimes I jokingly use the word whimsical. But it’s really intuition. I read something that sparks me. Unforgiven I read as a sample of [writer] David Webb Peoples’s work, figuring it wasn’t available. Francis Coppola had it at the time, and he couldn’t get it going. So I called up to ask about the writer’s availability for something else, and he told me it was available. That was a surprise. It seemed to me very timely.

How long have you owned it?

Since 1983. When I look back, I’ve kind of spun off of instinct and luck. The Outlaw Josey Wales came to me as a blind submission. I read it and liked it.

Is the kicking back at the end of a film — looking back at the accomplishment — is that the most satisfying thing to you, or is the process of doing it the satisfaction?

Some people are let down by finishing a project. I’m always elated to finish. Everybody has their pet part of it. I enjoy shooting a film, but I really enjoy when it’s all shot, and everyone has been excused, and I go to edit it with maybe one or two people. Then there is so much less pressure. There are not the thousands of questions.

Editing is your time of maximum control and yet maximum flexibility.

Absolutely. That’s where you can make or break it. That’s when you breathe all the last life into it. And you have to have all the pieces — the pieces have to be there.

Do you discover the film in the editing?

No. I discover it in the shooting. I know what’s there when I go to the editing. I may be surprised — it may play better or worse than I expected — but I pretty well remember everything I’ve done.

It’s anathema to you to go out and shoot a film and not be sure what you want to get, the way some directors do.

It seems . . . I . . . I just can’t conceive it.

Supposedly, one of the reasons you turned down Coppola on ‘Apocalypse Now’ when you were offered the role of Willard was because there was no ending to the film.

There were also several other problems. Francis had been talking to Steve McQueen, and Steve had then recommended me. Steve wanted me to play Willard, so he could play Kurtz. I said, “Steve, I thought they wanted you for Willard.” And he said, “Well, I want to play Kurtz.” I said, “Why?” He said, “Because I can do it in two weeks!” I said, “That’s great, but what makes you think I want to work for all this time?” Then later, Francis called — and I had just bought a house, and my children were very young — and he said they were going to go to the Philippines for sixteen weeks. It was just too long. If it were eight weeks, I would have done it. And I said I didn’t understand the ending. He said they were going to work on that. But anyway, two years later they were still shooting, and Martin Sheen had had a heart attack, and I thought: “Goddamn! That could be all of us!” I saw the documentary [Hearts of Darkness], and it was terribly amusing. Francis is a nice guy and everything, but two years — I would have gone insane!

I bring this up because you’re a guy who is known for coming in under budget and for wanting first takes.

Well, I don’t get first takes all the time, but I want them, yes. Once in a while you get great start-up actors — Gene Hackman and Morgan Freeman are great examples. They’re the kind of guys where you start rehearsal, and it looks so good you say, “Wait a second, stop, roll this thing!” because there’s no reason to be wasting it. They’re ready to pull the trigger right away.

You distrust rehearsal anyway, don’t you?

Well, I don’t like people to get stale. I like people to do things naturally. I like things that come accidentally. I guess it comes from years of seeing something nice happen in a scene and then not ever being able to see it come up again. Usually a good performer can drag it up again, but it may never have that spontaneity. So I do make an attempt to always get that first take — there may be lighting problems, technical problems — but you’ve got to be, like, stepping up to bat. You’re not stepping up to bunt. You’re stepping up to hit the damn thing.

Once, you said, “The more time you have to think, the more time you have to screw up.”

Yeah. The more time you have to kill things with improvements [laughs].

You end up with a bureaucratically imagined movie.

Yeah, exactly. And the movie can have a spirit like that. You get the feeling that the movie is wrung out. That it’s been all squeezed out before they ever printed the take. I like the inspiration of the first take.

What’s jazz taught you about film?

That improvisation can work well as long as you have the structure, as long as the tune is playing. As long as you know what the tune is, everyone can reach out. Actors who are acting generously are very much like jazz musicians: They are within the scene, but they are doing things that aren’t exactly written — the unspoken word, the notes they are throwing in.

Do you ever feel ambivalent about your work once it’s over and done with and out there as a part of our culture?

Yeah. Sometimes. I don’t think about it that much. I don’t know whether it’s callousness or whether it’s a . . . I just don’t think about it.

What about when the work talks back to you through the culture? Witness the celebration of the “Make my day” line.

I knew when I did Sudden Impact that “Make my day” would be the key line to the whole picture just when I read it on the page. Now, I didn’t know it would go like it did. People flew banners with it here, above the golf course. After a while, I really got sick of hearing it.

This may have to do with Eastwood as star as opposed to as director, but people impose agendas on you. In the Seventies you were a fascist, and in the Eighties you became a feminist —

And just what anybody wants to put in there! I was probably more a feminist in the Seventies, certainly more than I was a fascist, that’s for sure. I remember when Dirty Harry was offered to me. It was offered by an executive who said that Paul Newman had told him about it and had said it’s a great script, but he couldn’t do it, because of political implications. It disagreed with certain feelings of his. Well, I read it, and I said, “I’ll do it.” What works for me is, I don’t give a damn if I disagree with the guy or not — it’s a lot more challenging for me to play someone who I really have nothing in common with. That to me is acting. And the fact that people think you really are someone is really not an uncomplimentary thing. Because if you’ve affected them that much that they think you are this guy and that you have this guy’s philosophy, then you have done your job.

Well, indeed, you more than most actors are assumed to fully inhabit the role to the point where you and the role are considered a kind of “unit of meaning.”

That’s the way it should be. That to me is the fun of acting. That’s the way I’ve always thought. Both Don Siegel and I had a great time doing Dirty Harry in 1971 — we were both pro victim’s rights, but we weren’t anti accused rights. We just thought: “Here’s a story that talks about the victim’s rights. Okay, we’ll do this story.” Now, if there was a great story about the rights of the accused who had been railroaded into prison, it would have been just as exciting to play that.

Are you telling me that all this time you have actually been playing against type? In the westerns? In the cop pictures?

[Laughs] It’s disappointing. I’ve run into young people along the way, and they are disappointed if I don’t pull out a gun. I used to have guys, after Dirty Harry, pull up next to me and say, “Hey, call me an asshole like you did in the picture.” People ask me to say, “Do you feel lucky?” I can’t. I played it at the time. But now I couldn’t say it without laughing.

What was Don Siegel talking about when he said: “You can’t push Clint. It’s very dangerous. For a guy who’s as cool as he is, there are times when he has a violent temper”?

Well, that was the old days.

You’re mellowed now.

I hope so. He knew I could kick off. But we were young guys, hanging out. I could channel my temper into being in touch with my anger for the role. Channel it into another energy, for the most part.

Subvert all that free-flowing hostility into your roles?

Maybe. Maybe. You’ve got to have that love-hate thing with your audience. If you love ’em, they won’t respond to you. [Pause] I never hated them, but I made them reach forward to me. I feel like if they lean forward, and they see that they’re interested in what I’m doing, fine, but if you get to placating the audience, it becomes condescending to them, and then they’ll feel that. Maybe they won’t seem sensitive at times, and they may ignore you when you do your best work, but by and large they are cut in to the whole thing. And that’s how they pick the people they want to embrace.

You’re thought of as being quite close to your audience, and yet I’m wondering if there have ever been times — perhaps at the height of your commercial success — if it didn’t bug you that the audience was just wanting the same thing over and over. I mean, even the most sensitive, saintly artist would be driven to —

Driven mad, yeah! When you reach out and try something different, and the audience doesn’t go for it, it makes you wonder what the hell is the matter. You’ve got to be philosophical about that. You can’t think: “Well, I’ll just do genre flicks now. If they want killing, I’ll just kill. If they want mayhem, I’ll out-mayhem myself.” If you succumb to that, you become a self-parody. And I’m not interested in that. One good thing about having a certain amount of commercial success is you can afford to take a timeout. If you don’t, it’s kind of crazy, because you have only one career and one lifetime. If you look back on it, and you’ve made sixty westerns and forty cop pictures, it’s sort of empty. Now, a lot of guys may be happy with that: “Hey, it’s great, I can go out and golf and hit the ball on the weekends, and I really don’t give a crap about anything.” But I like films, and I like making them, and I like seeing them, and I grew up watching a lot of different kinds of films and different kinds of actors, and I think it’s spread over into my life.

Let’s talk about the Eastwood hero. I’m sure there are a hundred different times to say about this character and as many exceptions as rules, but one thing that does strike me is that the Eastwood hero is a deeply damaged guy who has been profoundly hurt and is acting out of that hurt.

I think so. I think the heroes all have something that is nagging at them. Dating back to A Fistful of Dollars and those stylized things. Most of the heroes I’ve played have definitely had something in their background that’s painful. Up through Unforgiven, where he’s really got damage. Through some pain, through some trial and error, through some suffering in life, you come to what you are. And guys of great strength who get things done — whether escapist heroes or not — have to have something in their lives to bring them to that point. They couldn’t be guys who just had a normal life — a normal job — and this fell into place. It just can’t happen that way.

Would you say that you’re one of those sorts of guys?

Are you looking for a parallel in my life? [Long pause] I don’t know. I don’t get into a self-analytical position very often, and I try to avoid it. I could say that I have the ability to take the things in my life — the hurts and disappointments, whatever — and channel them into moving forward, channel them into a positive force.

Did you feel your roles were tapping into something that was not a stretch for you? Obviously, you didn’t grow up as a gunslinger, but you were a lumberjack and a gas pumper and a —

I beat around. I had my beat-around years and my years of being lost. Lost in that I didn’t know what I wanted to do or what I thought I could do. But I’ve never sat and analyzed how they fit in. I think it’s strictly an imaginative thing. Just as you can imagine something positive in someone’s life — a force going forward — so can you imagine a background that’s slightly damaged. It’s just the imagination of the actor. You have to give yourself that obstacle to make the character interesting, to give it some depth. It can be somebody who has really had some pain in his life, like the outlaw Josey Wales or William Munny in Unforgiven.

The wounds those characters carry are profound.

It just takes a little imagination to do that. They are all suffering through a lot more than I’ve suffered in life.

I’m not going to ask you for more self-analysis than we were traipsing by there, but I’d like to ask you, parenthetically, why you don’t want to get into a self-analytical mode.

I just . . . it’s not out of fear or anything, it’s kinds like if I know too much about it, I’ll wreck the ability to do it. Really, you’re taking an art that is not an intellectual art form, it’s more an emotional art form, so you approach it on more of a gut level, and you’re bound to have better luck with it. The analytical stage only becomes how we’re going to do it, how we’re going to present it. I don’t want to take the spontaneity out of developing the character. It’s nice to find things out as you go.

Another aspect of the Eastwood hero is his fundamental and overriding decency to others — but when riled, a sort of termination with extreme prejudice.

Yeah. Yeah, that’s true.

They are not characters that bend. They snap.

Yeah, they don’t just bend. They are loyal characters, but when they’ve been wronged, yeah, they snap. That’s something I’m attracted to, I guess. I find that appealing.

Is the fascination for you in what makes him snap?

What makes him snap is always interesting. What was so fun in playing this current character is that he’s sort of forced by lack of prosperity into doing the only thing he really knows how to do well. And he has bad feelings about that, and he keeps bringing up his own demons — people he has killed. There’s a morality. It’s not like doing penance for the mayhem I’ve created on the screen over the prior years, but in Unforgiven, it’s the first time I’ve read it in a way, have been able to interpret it in a way that death is not a fun thing. Somebody is in deep pain afterward, even the person who perpetrates it.

There are consequences to the violence.

There are consequences all the way down the line.

Now, one of the things you’ve been slammed with over the years is that your pictures don’t show the consequences of violence. They show the bottled rage, the explosion — which is very cinematic — but they are weak on the consequences of violence, emotionally and otherwise. This picture changes that formula.

Yeah, it does. And I think that was the big appeal to me when I bought it in ’83. I sort of nurtured it. I put it away, like a little, tiny gem that you put on the shelf and go look at it and polish it and think: “I’ll do this. Age is good for the character, so I’ll mature a little bit.” Three years ago I decided I’ve got to do this. And today a lot of the stuff that has gone on this last year and a half, where a decision is made that is maybe not the right decision — where force was used to the extreme, like the Rodney King incident — is like Hackman in Unforgiven.

Why do the repercussions of violence matter to you now when they didn’t matter to you so much before?

I think just generally changing in life. Hopefully, we’re gaining more knowledge as the years go by. I’m not smart enough to have written it down, so all of a sudden I say, “That’s it, that’s the element that’s been missing for me, that I haven’t been able to deal with properly.” Maybe skirt here and there but not really explore it.

The world of ‘Unforgiven’ is a complicated world. It’s an adult world: It’s a world where violence doesn’t solve any problems, it just changes the problems. That’s a sea change for you.

Exactly. And that was very appealing to play and to explore. We’re talking about people purging themselves and changing attitudes — I remember when I first spoke to Gene Hackman about playing this role, he said, “Well, I don’t want to do anything with any violence in it.” I said, “Really?” He’s had his share of violent films, too. I said: “Gene, I know exactly where you’re coming from. I’ve been involved in a lot of violent films, but I would love to have you look at this because I think there’s a spin on this that’s different. I don’t think this is a tribute to violence, and if we do it right, it’s not exploiting it; in fact, it’s kind of stating that it doesn’t solve anything.” So when he read it, he could see where it was headed, and he decided to do it.

Did you relish de-mythologizing your persona?

Yeah. It was nice. It was fun. And you’ve got to be uncompromising there, too; there’s nothing glamorous about it. He’s a guy who’s pretty much on the bottom.

What about de-mythologizing the West, the “Wild West”?

I didn’t mind that either. Because it’s been de-mythologized along the way. It’s great to do it because I didn’t have to work at it; it was there as part of the nature of the story. It was in the structure and the honesty of it. It was odd to start out with a guy who’s quite inept. He’s having trouble getting on his horse [laughs], he’s rusty. It’s different than the characters I’ve played, where of course they couldn’t miss with the gun.

And I don’t think there’s ever been a western where the fear of death is discussed so openly. Munny sees the maggots at the door, so to speak. Tell me about your attraction to this idea.

The first philosophizing about death is when he’s reminiscing about killing the guy whose teeth he shot through the back of his head; he’s haunted by the memory of this guy who didn’t do anything to deserve to get shot. And then when he has fever, he starts hallucinating, and he sees a guy with maggots crawling out of his head. He’s constantly pursued by the visual image of what he’s done in the past. Or images he’s seen. Like for a guy who’s been to war. Like for a guy who’s seen the Lieutenant Calley [My Lai] massacre.

Like for the guy who’s made violent movies and carries around a lot of visual images from those movies in his head?

[Smiling] Well, I don’t know if that’s analogous. . . . It could be that the guy has all those violent images portrayed on the screen, and along comes a piece of material that allows him to do something that he’s never been able to do in the past — which is to show where it all leads to. To philosophize about, what is the value of it all?

Did the Rodney King tape get to you?

[Pause] Yeah. First time you see it, you’re overwhelmed. You’re overwhelmed — boy, seems like a little much to me. Course, you don’t hear anything or see the prelude to it all. But anyway, under any circumstances, that seemed excessive. But then I got tired of it, and I got mad at the media for running it — ’cause I think they are exploiting it. The exact same people that are critical of the exploitation of the violence are in there exploiting it every time they can, running it again and again. The media has gotten so callous. It’s all one-upmanship for ratings, so that’s annoying. But without knowing it, there are certainly parallels to what goes on in Unforgiven.

In this film, the punishment never fits the crime. It’s never about justice but about vengeance meets commerce, which I guess is what a bounty really is.

Justice never becomes part of it.

Justice is never even on the horizon.

Yeah, justice doesn’t have anything to do with it. It’s about conscience more than justice. [Long silence.]

Leaving this movie, I couldn’t imagine you playing a comic-strip action character again.

Yeah, I probably can’t. I think the days of me doing what I have done in the past are gone. This is the present for me. To be saying smart lines and wiping out tons of people — I’ll leave that for the newer guys on the scene. And that’s just part of my growing process. I wouldn’t know what to do with such a thing now; I’d have a hard time concentrating on it. At one point, I could throw myself into that; now I need more of a demand. I don’t know how to equivocate it: It’s like you need more foreplay or something [laughs]. You need something better.

When you were finished filming the shoot-out in the saloon, were you conscious of the fact that that may be the last time you’ll do something like that?

Uh-huh [pause].

How did that feel?

It felt good. I was even conscious throughout the film that this might be my last western. This was the perfect story to be my last western. I also thought this might be the last time I do both jobs — acting and directing. Maybe it’s time to do one or the other. It’s funny, you’re the first person who’s picked up on that, but I did have a feeling when I was doing that sequence that it would probably be the last time I’d be doing that.

Earlier you said, unprovoked by me I might add, that you are “not doing penance” for all the other characters you’ve played. Obviously, that concept is on your mind.

I said that unprovoked, but I said that in such a way that maybe it is. I’m not consciously doing penance for the mayhem I have created on the screen in the past, but in a way it fits in. Because he is a man that is haunted by this experience. I think it’s not a conscious thing to do penance — if I hadn’t done those other pictures, nobody would even think about it. But like you were mentioning, a lot of those people had things in their backgrounds that were kind of painful. This is the first one where you know all about it. He’s been involved wish some pretty bad mayhem in his day.

Another thing that shows up in your work is an attachment to the downtrodden. I can’t believe that you’ve blundered into these characters accidentally; there’s clearly a selection process.

I probably have an affinity for the underdog, the downtrodden, the depressed. Who knows why? Either it’s dramatically or being raised during the Depression. I don’t know. Seeing a lot of that growing up in the Thirties. I don’t know. I’ve never analyzed it. I never had the ambition to. Somewhere along the line there’s some inkling that makes you gravitate towards a certain type of thing.

The downtrodden underdog, which your film persona is so attached to, seems quite different from your public persona away from the screen as a card-carrying Republican. Society tends not to view Republicans as critters who have that sort of affinity. That tends to fall to Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition.

Well, I’m not in any of those camps. I’m not in Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition, and I’m not in the Republicans’ camp. I became a Republican only because when I turned twenty-one, Eisenhower was running and I wanted to vote for him as opposed to Stevenson. So I did that. And also, the Republicans were a minority, and it’s fun to be part of a minority. At that time they were outnumbered in California. So I just became that. Actually, my views are probably leaning toward a libertarian point of view.

You’re a bloody anarchist!

Not liberal. Liberal always has the connotation of somebody that wants to spend somebody else’s money. And conservatives don’t want to spend any of their own money. But libertarians love independence, and I like everyone leaving everyone else alone. I’ve never approved of government meddling. Whatever people want to do is fine as long as you’re not bothering anybody else.

So you’re looking for a fusion of Milton Friedman and Noam Chomsky.

Yeah, exactly!

You get those two guys together, you’ve got a ticket.

You could. You’ve got a much better chance of getting those two guys together than some of these guys we’ve got now.

Let’s look at your greatest stretch-mark movie: ‘Bird.’

Left stretch marks inside my brain, just over the cranium.

Spike Lee was quite upset with ‘Bird.’ He told me, “How is it when Clint Eastwood makes a movie about Charlie Parker, that the two other most important people in the movie, Chan Parker and Red Rodney, are white?”

You know, it’s a shame to take — and I think it’s reverse racism, although I’m sure he doesn’t quite know what he speaks of, I think he’s a clever kid — but it’s ironic to take jazz, which is at the forefront of all integration in this country or anywhere in the world for that matter and in the early days in New Orleans, where people were judged just by what they did and not by their color —

Well, the music simply would not have existed without black and white coming together.

Exactly. And they were the predecessors of all integration in this country, and jazz is the truest American art form. And for some guy to come along now, in the Nineties, and try to segregate it in his mind, is . . . so, I don’t know what Spike Lee is talking about. I think he was just shooting from the lip a little bit. I wouldn’t be prejudiced if he wanted to do a thing on Mozart or Beethoven. More power to him. From a director’s point of view, being a black man doesn’t preclude you from doing a white story.

I’d like to bring up the epitaph of the film, which is Fitzgerald’s “There are no second acts in American lives.” The quote was fitting for Bird, but do you believe in the concept?

It seemed fitting for him because he was only going to live the one act. For me, no, it’s a three-act play. I hope [laughs]. Hopefully, the play pyramids and doesn’t falter in the end.

Miles Davis, Bird’s old sideman, had about five acts in his.

Yeah, he had a lot of different facets to his career. He had that wreck in the Lamborghini, he retired and had all his drug and booze problems, but he came back. I first met him in Seattle. I was doing Rawhide at the time; it was quite a few years ago, in the late Fifties or early Sixties. He wasn’t with Coltrane. And he came over at intermission and asked me [imitating Davis’s hoarse rasp]: “Will you send a picture to Miles Jr.? Miles Jr. is a fan of yours.” I said: “Sure, Miles. I’ll send one out.” Then he told me to hang out, and I said I would. So after the set he came over and said, “Let’s go out and get some bitches.” So we went out to some after-hours joint; Seattle was kind of a closed town, but these clubs would last till way in the morning. So we went out and screwed off. Man, he was a character!

Are you thinking more now about forgiveness and redemption — the themes of ‘Unforgiven’ — than you did as a younger man?

Maybe by getting the property at an early age and setting it aside until now, I was preparing for a certain time. I don’t know. It delves into things I wanted to delve into. We as a society grow more tolerant of violence, of accepting life and death in the streets, and we don’t seem to put our foot down. We get hardened.

We accept a higher and higher level of despicable behavior.

I know it. As our society drifts that way, maybe, from my point of view, it was time to analyze it from how it affects people. The perpetrator and the perpetratee.

Outside the golden rectangle of Hollywood projection, are things not going in our society the way you thought they were going to go ten years ago? Were you more hopeful then?

Maybe. Sometimes you just wonder. It seems like the entertainment and communications industries have become so big, and they are so competitive that it seems like as far as violence and mayhem go, there’s a great competition to get it meaner and deeper on the front page of every paper. You got to beat the guy across the street. We see a lot more than we did years ago. Vietnam brought war into the living room. And now the Rodney King beating runs 57,000 times on television. That’s the commerce, that’s the capitalism of the electronic media: How do you cut to the most blood? Maybe there is a penance there. Maybe that’s why Gene Hackman didn’t want to be involved in violence.

Action pictures now make ‘Dirty Harry’ seem like ‘Oklahoma.’

Oh, yeah, like nothing. You look at pictures where people are dismembering people and saying, “Here, let me give you a hand.” Dirty Harry would never do that. Dirty Harry just wanted to rid the streets of the antisocial people working against society. But now it’s like everything is mobs of mayhem out there: Cut ’em up, kill ’em up, dismember ’em, cut their heads off. I don’t know what effect this has on society. Maybe none. I grew up with Jimmy Cagney and Humphrey Bogart blowing guys away and John Wayne, but everybody knew the difference between a movie and reality.

There wasn’t even a ratings system during the Crusades, and there was plenty of violence.

Yeah, there was more mayhem created in the name of God — my god is more right than yours. But in the Sixties and Seventies, we were entering into the fall-guy generation, and we’re at the peak of it now, where nobody is responsible for their own actions. It’s like “I can’t help the way I am; my mother accidentally backhanded me when I was a kid, and she had PMS.” There’s all kinds of reasons for things; instead of people grabbing themselves by the gut and saying, “This is what I have to atone for.” But that’s the era we’re living in now, and it’s being bred into us. We see it in the paper all the time. It’s always somebody else’s fault. Right now, politically we get that: Is it the Congress’s fault or the president’s fault? Get with it; it’s everybody’s fault. But nobody wants to take responsibility. Congress is sitting there worried about their perks, and the president is worried about being reelected. Aw, shit!

But you’re happy just being the ex-mayor of Carmel!

I’m so happy. It was a two-year term, and council members are four years. About one year into it, I thought, “You know, Eastwood, it’s really nice this is only a two-year term, because that’s exactly what it’s going to be for you.”

Did it teach you anything about government in America? Anything printable?

It’s fucked [much laughter]. Whether it’s a small town or a big city, whatever the size of the playing board is, it’s the same problems. It seems like my best move as a politician is that I got in by a great majority, so I just made all my moves in the first six months. I fired the planning commission; I dumped, I changed everything — things that normally would be quite shocking I did quickly.

Seize the day.

I seized it, grabbed it, ran with it, and I got things done, like a library annex that had been pending for twenty-five years. I could have hung around for another term and done a few more things, but it would have been half of what I did that first term. Plus the fact that you can’t have a career. I did two films while I was mayor — Heartbreak Ridge and Bird.

No wonder ‘Bird’ was so dark; it was actually about the city council!

[Laughs] It was my city-council meeting! In Heartbreak Ridge, I was playing a character who I’d really like to have been as mayor. Stand tall and take names!