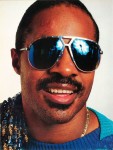

Stevie Wonder

WAITING ON THE MAN: STEVIE COMES DOWN FROM THE MOUNTAINTOP

WAITING ON THE MAN: STEVIE COMES DOWN FROM THE MOUNTAINTOPMusician

February 1984

So here we are sitting in this drab Radio City rehearsal room in hushed anticipation of a word-of-mouth press conference given by a pop superstar in honor of the birthday of a pol superstar; here we are waiting on the man, who is always late, having his own peculiar time-zone — a function of his brilliance and his blindness — and here is this gaggle of legitimate reporters and cooled-out music hounds, cyclopic cameramen and shuttering photographers, glinting security guards with walkie-talkies, professional hangers-on, members of the Wonderclan traveling roadshow, stringers, freelancers, black members of the black press and white members of the white press, black members of the white press and white members of the black press, waiting on the man.

To enhance the tedium and to sharpen the claws of our critical acumen (to stay in shape we exercise our opinions regularly), a few music hounds compare notes on the man’s ongoing week of Radio City shows. Good. Fair. Surprising. Were you at one where he did a lot of talking? He’s a funny mimic. Sometimes he’s funny. He should shut up and play some music ’cause he ain’t no comedian. I remark that the “Ebony And Ivory” routine that he’s been pulling every night on the tour — a routine in which Stevie asks some black folk and some white folk to come up on stage and sing the thing together as sort of an audio-visual aid to the “point” of the song—was oddly touching, even authentic, and reduced a hardcore cynic like myself who never could stomach the simple-minded syrup of both lyric and melody to bleeding heart wishfulness right there in row KK. Such is the occasional wonder of Wonder.

Also said I was sick ‘n’ tired of having to hear his royally tender ballads compressed into the grim fast food of medley after medley (hold the third verse, hold the chorus) and found that no amount of vocal grandstanding (assorted swoops and shouts, exaggerated melisma, dime store dynamics in the manner of Vegas) could make up for the emotional dryness of a greatest hits configuration. No one at the gig was thrilled with the new material (including a florid ballad called “Overjoyed,” and a P-Funked bottom stomp called “It’s Growing”) but we’ll all have to sit down with the new record and give it a hard listen. Should be out by 1986. But the show was fun and pleasantly loopy (including a dancing robot “Wonderoid”) and I won’t dwell on it any more than Stevie dwells on his non-hits. We were all left singing “Happy Birthday” for MLK, whose birthday — in large part due to efforts of Wonder — had just been rendered a national holiday by those enlightened slobs of self-interest down in Congress. Long overdue of course, like Mr. Wonder’s records.

We were still waiting for the man to arrive and make a statement about the above happy event when I informed some colleagues I had been promised an interview with the man himself. Colleague A informed me that she too had been promised an interview (for Essence) and colleague B — a major dude of correct complexion — informed us both that he would be having nothing to do with speaking to Stevie ’cause the guy was “an asshole, a bad guy.” Sacrilege! Scandal! Gadzooks! Wonder a bad guy? What about the Lovepeacecaringsharingegalitarian image? Shiver me timbers. True, two years ago I had a promised interview cancelled from Houston, airplane tickets hot in sweaty palms. But you figure: That’s Entertainment. The guy’s busy creating, let it slide. After all, he’s Stevie Wonder and we’re not.

After the press conference (in which Wonder read a prepared statement reflecting his joy and justified sense of accomplishment in establishing Dr. King’s holiday) Colleague A and I met with one of the man’s many assistants, who shuffled her cards and dealt them with an Attitude: “Look, Stevie’s voice is really weak ’cause of all the shows he’s been doing and he’s promised like six covers, so you’re going to have to pair up and do the interviews in teams, maybe over lunch in the next couple days. Don’t call us, we’ll….” Colleague A and I grumbled our way out of the building, imagining the scenario of a shared Essence/Musician Q-and-A:

MUSICIAN: Is it true that the harmonic distortion inherent in contrapuntal digitized drum computers decays the be-bop of not only chordal but microtonal lyrics?

WONDER: Uh huh.

ESSENCE: Stevie, this one’s a two-parter: what do you use on your hair? And have you found you wife’s G-spot yet?

WONDER: Johnson products and I’m still, like, trying, man.

■

But don’t dismay, music-heads; this reporter persevered and eventually was told that the man had narrowed his list of invited guests down to three magazines — Musician, Essence and, hey, it’s a star’s prerogative, The Muppet Magazine. As I dutifully prepared my questions, I reveled in the awareness that I had attained the same socio-cultural standing as Kermit the Frog.

The night I was summoned to Wonder’s Radio City dressing room—October 23—was cold, rainy and depressing. X number of marines in Beirut had just been extinguished (the big world) and on top of that, Stevie was coming down with a cold and feeling strange (our small world). While Stevie waits for some tea—without which we cannot begin the interview — an assistant comes in and places a PPG 2.2 Wave synthesizer on a slanting ironing board next to the table at which he sits, fiddling with an Aiwa synchro-dubbing cassette deck and a Sony with braille buttons. Stevie puts on a full range of his voices (Jamaican, Big Bopper, Munchkin, Little Girl) mimicking everything that’s going on in the room. Then for a bit he and his managerial consultant Ewart Abner talk about Lebanon and the new Russian missiles in Syria and the Soviets’ target practice on the KAL Flight 007, upon which Stevie had some friends. He asks me if I’m on the couch or the chair and comes to sit next to me on the couch while voicing his displeasure that a New York newspaper had misquoted his feelings about the John Bircher congressman who died on that plane:

WONDER: I don’t have any time for enemies, number one. And number two, there is really no one that I hate.

BRESKIN: It takes a lot of energy to hate.

WONDER: It really does. Really, a lot of unnecessary energy. You can definitely disagree, but it’s not worth the energy to hate. Because it doesn’t help anybody.

BRESKIN: Let me be boring now and take us back to the beginning, a very good place to start. What’s the first thing — either musically or otherwise — that you remember?

WONDER: Johnny Ace. I remember xylophones. And saxophones of some sort. Syrup and biscuits. Guitars, I guess Wes Montgomery. You know, I didn’t know who it was, but the sound. This is when I was two or three. Radio. This guy used to come on this station in Detroit, named Bristol Brian, Senator Bristol Brian they called him, came on in the morning on WJLB in Detroit. I remember rain. Rain, rain would make me think of corn flakes for some reason. The “Sundown” show came later. WCHB was the first black-owned station in Detroit, and was basically a daytime station that would come on at sunrise and go off at sunset.

BRESKIN: Do you remember playing the spoons?

WONDER: The spoons, very vaguely. I do remember them. I remember that I couldn’t play them, that’s what I remember. I loved the way they sounded. I was thinking the other day about the many different accompaniments that I’ve had: it was someone playing the spoons and me singing, or someone playing the guitar and me singing, or a bass and me singing, or me beating on a table or a wall and me singing. It’s amazing how many sounds so unlike the sounds of an instrument are happening now, because of the new technology of synthesizers — and being able to sample and sequence the sampling.

BRESKIN: There are a lot of sounds found in the world that people don’t hear as musical sounds, which now can be rendered “musically” through synthesizers. Having these sounds — let’s say they’re the sounds you hear on the street in New York — at your touch must free you up a great deal….

WONDER: Yes, it’s being able to sample those sounds. You can do it one time, and then you have it. And velocity sensitive keyboards help too. But nothing really can replace the naturalness of a sound. You are not replacing it—you’re just putting it on a chip or a floppy disc or whatever. (jokes) Now let’s take the sound of that bus, that would be a great sound.

BRESKIN: Are there sounds that you’ve had in your head for a long time that you’re finally able to realize now?

WONDER: Yeah, yeah. Like on The Secret Life Of Plants, a lot of that was different sounds that I wanted. The creation of the sound of the earth, and of life itself. Life has a rhythm — and as we did in one of the segments between “Earth’s Creation” and “Come Back As A Flower,” we created the sound of thunder and the crickets and the birds and other animals in rhythm. And that’s how life is. Life is a perfect rhythm anyway … to its own time signature.

BRESKIN: When you began singing in Detroit, you describe your attitude in your fan club solicitation with the sentence, “He sang for joy, seldom thinking of enumeration.” You’ve just sold out eight shows at Radio City and I take it you’re still singing for joy.

WONDER: Right. Music has consistently been a fun thing for me. And it will always be that. If it isn’t I will no longer do it. And if I stop — if I eventually decide to just produce or write — it will be fun to do that. So it will never be about just being able to make money, but to do it and enjoy it. I can’t say it’s been a hobby, because it’s been greater than a hobby. It’s been life.

BRESKIN: Have you thought about not performing live?

WONDER: Well, we don’t do that much anyway. But eventually we won’t do as many performances. But I think the neat thing about this particular tour, which I call affectionately the “You And Me” tour, is creating a whole vibe of being closer to the people and sharing with them things about me that they may not have known. And going through a lot of the music we have done, because if we do some more albums there will be things we’ll no longer be able to do. ’Cause we just can’t keep adding on and not take anything out of the shows. So this is probably one of the last times I’ll be doing this kind of show.

BRESKIN: Radio City rather than the Garden, theaters rather than arenas?

WONDER: Right. Because it gives me a chance to really be closer to the people and to share those moments ….

BRESKIN: The living room atmosphere, talking to the audience, engaging in some casual interchange with them ….

WONDER: Yeah, I enjoy these things. It’s different. It’s not boring. It’s fun. It has a beat and you can dance to it.

BRESKIN: Were you ever bored by performing? You’ve been doing it steadily since you were nine or ten?

WONDER: I think maybe in ’71, ’72 I was bored a little bit. Partially because (huge sneeze), hold on….. (Stevie walks into the bathroom and gets a tissue. As he walks back to the sofa, he says loudly, feigning virus warfare: “There’s a cold ’round here and I ain’t gonna catch it.” Now imitating a baadd funkster, he tells himself: “C’mon now, get it together. Everybody put your hands together, c’mon.” He pauses to drop some peppermint oil down his throat. “It busts everything right out.” He settles back down on the sofa. Abner, who’s re-entered the room, with cups, asks if he wants the licorice tea. “Are they capsules?” Stevie asks. Abner says yes, and opens the jar so Stevie can feel the capsules. Abner asks, “Is one all right?” “One is good,” says Stevie. Abner puts one in. “But two’s not bad.” Abner puts in another capsule.)

You know, you’re on the road and they say (now imitating a crusty, old condescending doctor) “Oh, boy, all you need is some penicillin, penicillin shot’ll just knock it right out.” But I never liked needles anyway. But the way to get rid of it is naturally. Walk out in the rain. We were on something ….

BRESKIN: We were on being bored with performing.

WONDER: Right, in ’72. It was the same old same old same old. And there was really nothing musically happening for me. And then “Superstition” came out around October of that year, and that put things in perspective. And in ’73 we had Innervisions. The only bad thing about this time was the accident — but maybe it wasn’t bad, because the accident made it necessary for me to cool out for a few months.

BRESKIN: It’s been ten years since the accident (a near-fatal coma-causing car accident). Do you see it as a pivot point in your career?

WONDER: I think subconsciously it made me more attentive to my life. My own self, inside, more than anything that anyone could physically see. I think we were rushing a lot back then, and performing a lot and moving a lot. I’m not saying we were living a wild life, but that was the direction things were going in. There was no true direction. “Superstition” happened, and I hadn’t expected it to happen, or happen that quick.

BRESKIN: You said at the time that the accident made you aware of many things you had done that you wanted to correct.

WONDER: And those for the most part were things dealing with being out there on the road. I mean, we weren’t doing anything crazy, but maybe there were some things that could have led to craziness. It gave me time to think. It was more the kind of environment than anything else: the things I could have been accused of doing. And I think there are times when you have to put a stop to any space that is not advantageous to your growth.

BRESKIN: What were your memories of being out on the road with the Motortown Revues?

WONDER: The Motortown Revues were fun. A lot of it I could not know or participate in day-to-day because of the school curriculum I was on. When a lot of the people would be asleep I’d be up studying with Tad, my teacher. And then when they were up partying and having a good time, I was in bed. So I missed a lot of what was going down (snaps his fingers). But I was there and I loved it.

BRESKIN: When did you — either consciously or naturally — feel like you had made the transition from being a novelty act to an artist, a more independent, creative musician?

WONDER: I never acknowledged, “Hey, I got to be this kind of artist.” I always basically flowed with things and I’ve always felt I had something to offer, something to give. But I didn’t try to burden anybody with the fact that I felt that way. I more so just wanted it to happen. And that’s why it took from 1966 to 1969 for “My Cherie Amour” to come out.

BRESKIN: I know you had to fight to get it released and when they released it they put it out as a B-side.

WONDER: It was just that the various people at “quality control” felt it was not the appropriate song to make an A-side. So they put it on the B-side of a song I wrote with Don Hunter, “I Don’t Know Why I Love You.” And that was more of an underground slight hit: it showed some changes, like putting the clavinet down at a low octave, and that sounded different, and the repetitious vamps started happening. It was influenced by Otis Redding’s “That’s The Glory Of Love.” But “My Cherie Amour” was a song I had in the can — in my own little can, which is my tape bag, that I carry around — for a long time. And I played the song for Hank Cosby, who liked it a lot and came and produced it. Originally it was “Oh My Marsha” but Sylvia Moy came and changed the words to “My Cherie Amour.” I had a girlfriend named Marsha. Well, we broke up, so it was a good thing they changed it.

BRESKIN: But it wasn’t a “Motown Sound” tune, and therein lies the rub.

WONDER: No, it wasn’t. And I don’t even think they knew what to do with me at that point. We were getting some misses and some mild hits. It was almost like, every other year we had a hit.

BRESKIN: Now in your shows you tell the audience about the dry period between “Fingertips” in 1963 and “Uptight” in 1965 where the company was determining who was “overweight” as you say, and some people thought it was you. And wanted to drop you.

WONDER: Oh, yeah. Straight out. And probably if I were the president of the company I’d do the same thing. Straight out. But fortunately, it all worked out … to everyone’s surprise, or to some people’s surprise. Because some people would say things like, “Oh, that boy’s gonna really be great. You don’t know how talented that boy is.” And the others would say (intoning superior disinterest), “Yeah, yeah, yeah, uh-huh, sure.” They didn’t really vibe on me. Now James Jamerson and Benny Benjamin always said I’d be great. I had the confidence that something good was gonna happen but I didn’t know when. And then … it begin to happen.

And the funny thing is when it started happening I didn’t use a lot of the Motown musicians. I used Pistol, the drummer, and I think James Jamerson played on “Signed, Sealed, Delivered,” but a lot of the things I was doing had, say, the influence of Stax. If Stax Records had done something with the kind of groove I liked, well … I did “We Can Work It Out” with a Stax kind of groove. And a lot of the Motown people didn’t understand that. I had a desire to move out of the one little thing that the musicians were in, and that Motown was in. And I wanted to do it, hey, because I liked the groove.

BRESKIN: Did you encounter resistance from the company?

WONDER: Well, I don’t know if it was “resistance” so much as, “I don’t understand what you’re doing,” and “Hey, it’s not happening.” But then it happened. Berry (Gordy) did like “Signed, Sealed, Delivered.” He did like that.

BRESKIN: Do you maintain a close relationship with Berry?

WONDER: We’re fine. He’s one of the nicest people I know. I like him as a person. I like his thoughts, his logic, and I understand it far better than I did when I was younger. That isn’t to say that we always agree on things, but I don’t think it would be fun if we agreed upon everything. I understand his attitude, his feelings. He is a great man.

BRESKIN: Will you be at Motown ad infinitum? The thirteen million dollar contract you signed in ‘73 amid all that publicity was a seven-year deal.

WONDER: We’ve signed since then, again. And we will always sign again, and we will change some of the terms of the agreement. But basically I will have a relationship with them as long as there is a Motown. If it is no longer Motown, I don’t know if I will do that.

BRESKIN: When you signed the contract in the mid-70s, you did so, you said, because Motown was the only “viable black-owned company.” There’s a tricky balance between vigilant support for your own people and heritage and your universal message about “brotherhood” and the erasure of color lines.

WONDER: Yes. Well, see, my thing is this: my attitude with Motown and with Berry and with it being a black company is a very simple thing. Uh, the fact is that society had written Berry out as a loser. Right? Basically. Before he was anything, he was written off. No one expected it to happen — and that’s why it happened. No one ever thought in a million years that from Detroit, Michigan there would be some guy — let alone a black guy from lower middle-class, from a family of carpenters — to create this music in a place where people didn’t even know music was happening. I look at them as a family. I think there is nothing wrong with being part of an achievement of your culture, particularly when there are not that many in comparison that are recognized. So I say, “Listen, for as long as our relationship is satisfactory and we are comfortable with what we do, I will be there with you, because I want to be part of that history being made.” I would want someone to say, “Well, Stevie Wonder, while he was alive, stayed with a company owned by a black man for forty years.” Or however many years it turns out to be.

The fact that we have to say “black” or “white” — as I say in my show — is unfortunate. But it does exist. That isn’t to say that we are going to deny anybody else anything. My thing is: I love everybody. I love people. And even though I can’t see, I do know colors, and I can tell people’s personalities and their attitudes and the whole thing. I’m usually clear on that. But a lot of the other companies, they can get anybody they want. And that’s been proven — they’ve gotten most of the Motown acts. And that’s great for whatever that is. But I think for me, I would like to see a certain amount of stick-to-it-iveness, and just being there for those people that basically don’t have anything and look up to this. They can say, “Oh, it can work.”

It’s like when I see a group that’s been together for a long time. Like the Four Tops; and there’s another group, they won a Grammy, a white gospel group. And it’s just great to see it, to see that kind of unity. Now sometimes you disagree, and you fall out and whatever. And that’s natural. And maybe I won’t be there for the duration of Motown. But I’m almost sure I will be.

But wherever else I do go I will have demands that I will expect to be respected. For instance, lots of times I deal with different businesses, and I don’t say, “You should only hire blacks.” I say, “You should hire various people from various cultures to be a part of it.” In our radio station in Black Bull, we’ve begun to hire … various people, white or whatever. Because, even though people say, “Oh, hey, what do you think we are, a checkerboard or something?” I say, “Yeah, man, you are, you are.” This is supposed to be melting-pot country for lots of different people.

BRESKIN: Right, like how many children did Thomas Jefferson have by his slave mistress, Sally Hemming? Not too many white people around named Jefferson and Washington. It’s written all into our nation’s history.

WONDER: Exactly. It’s got to start somewhere. And if we don’t start it, who will? Do you follow what I’m saying?

BRESKIN: Very much so. Dr. King was an integrationist, and there were people on both sides that criticized him, especially the more radical black leaders, towards the end of his life.

WONDER: I don’t even think he was that popular when he was killed. He was popular to those people who were really sincere. (The door opens, an assistant looks in, and closes it. Abner comes in.) Hey, tell these people not to keep coming in and bothering me. It’s blowing me out of the box. Plus also, if we don’t get a lot of what you need today, I’ll call you on the phone and you can get some more. It’s most important that you get as much as possible. So make sure you give me your number. Is it about 6:30 now? (I look at my watch; it’s 6:31.)

BRESKIN: I wanted to ask you about how you compose, about the process.

WONDER: It varies. But for the most part, I come up with the music first. The melody. And then I will come up with the basic idea for a lyric, the punch-line, and I’ll put that down. And then I’ll come back later and finish up the words.

BRESKIN: Ever try different sorts of lyrics with the same melody?

WONDER: Once I have the melody I usually don’t change. Oh, well, we were going to write some really crazy words for the song, “I Wish.” Something about “The Wheel Of ’84.” A lot of cosmic type stuff, spiritual stuff. But I couldn’t do that ’cause the music was too much fun—the words didn’t have the fun of the track. The day I wrote it was a Saturday, the day of a Motown picnic in the summer of ’76. God, I remember that ’cause I was having this really bad toothache. It was ridiculous. I had such a good time at the picnic that I went to Crystal Recording Studio right afterward and the vibe came right to my mind: running at the picnic, the contests, we all participated. It was a lot of fun, even though I couldn’t eat the hot dogs—that was around the creation of those chicken hot dogs. And from that came the “I Wish” vibe. And I started talking to Gary (Olazabal) and we were talking about spiritual movements, “The Wheel Of ’84,” and when you go off to war and all that stuff. It was ridiculous. Couldn’t come up with anything stronger than the chorus, “I wish those days (claps) would (claps) come back once more.” Thank goodness we didn’t change that.

BRESKIN: Are you generally quick to lyricize, or does the music sit around for a while and filter in and out once you’ve put it on your cassette?

WONDER: The point of lyricizing is that I do come up with the basic idea; the basic melody and lyric idea from the feel of the song. I get that, and then it depends when I’m going to write the lyric. “Overjoyed” from the next record, I wrote the lyrics about a year after I had the basic idea in my mind. And I didn’t do it all at one time.

BRESKIN: In what sort of state is your stash of ideas, your storehouse of working tapes?

WONDER: Well, because of technology, it’s changing a great deal. I could play a demo for you and it would sound close to the almost-finished track. ’Cause I feel you should stick with the feel you have at the beginning of something. Unless, of course, you can make it better. I keep everything right now on Betamax tape.

BRESKIN: Do you have virtually hundreds of snippets of music, unfinished business, that you keep as an aural notebook, or a refresher of where you were?

WONDER: I don’t do that so much, because if I have something I try to finish it up. I have some of that, though. But I want to finish it up so that it makes a complete statement, as much as I possibly can at the time.

BRESKIN: Will your recording change at all in the future, more towards the one-man productions and away from the group things?

WONDER: Ummm, I think I always want to keep a balance between the two. But one record may have more of one than the other. I see a picture of a song being one way or the other. For something like “Sir Duke” I saw musicians and I just went about getting them, but for something like “That Girl” you just basically do it yourself.

BRESKIN: What’s the biggest change in the last year or two as far as what information is accessible to you?

WONDER: I would have to say my reading machine. I’m able to put a book inside this case that has a camera. The camera scans around the page, and converts all that information to digital information and then converts it again into voice synthesis. So I’m able to read a book, to read a printed page.

BRESKIN: So the machine will “talk” the book to you? A Talking Book if you will.

WONDER: Yes, right.

BRESKIN: Can you travel with this?

WONDER: I have traveled with it. But it’s kind of cumbersome and it can break. It’s called the Kurzweil reading machine and I think Xerox is handling it now. It comes from Boston. It takes time to get used to the voice. It’s a computer voice.

BRESKIN: I want to talk to you about the simplest and most difficult thing in the world, love, which is certainly the focal point of your concerts and many if not most of your lyrics. When you say — and you have the audience chant — “Love Is The Key” I want to know what you mean by love. If you can’t define it, that’s fair too.

WONDER: When I say “Love Is The Key,” I really mean love is the key. Putting love to anything, bringing it into anything, understanding, trying to really give the positive of something — it could be a personal relationship or a business or whatever. If you deal with the spirit of God, the spirit of love in your heart, with sincerity, that’s the key. That’s what I mean.

BRESKIN: What’s the distinction for you between romantic love and the sort of love you’re talking about here?

WONDER: Well, they’re different emotions. But they all are very emotional things. You know when a mother is breastfeeding a child, it’s not the same vibe as … as … (laughter). That’s a good analogy, huh? But when you’re kissing your child you don’t think of kissing (laughter) you know ….

BRESKIN: Now there are some sick folks on the coast ….

WONDER: (continued laughter) When you say “I love you” to your mother, well, it’s different. But it’s still love in your heart. That’s why I see no reason to create any kind of negative thing, even though I may say things that throw people off if they have a preconceived notion of where I’m at. It’s like on television, you never see people use the bathroom so you think they must not.

BRESKIN: Because love is a unifying principle for your work, and you have, of course, very strong romantic impulses in both your music and lyrics, you’ve also been criticized for indulging in mawkishness, excessive sentimentality and the like. How would you respond to this?

WONDER: You’ve got to remember — as you know and as everyone does know — that love is somewhat a sentimental thing. Love is about those moments of ecstasy … and then you wait for another one to happen. And you think, “Remember the first time we kissed,” or “Remember when we went out to the zoo with the kids,” or, “Remember that time when we played all night and just played and played and the band was cooking.” That’s the beauty of it — it is only as permanent as you make it. That is what making love is all about. Not just about physically making love, but creating love in the now for tomorrow. You have to create it for tomorrow, for that now — which you then look back upon, with the memory of moments.

So basically, when you’re writing a song you’re creating a short story of a love emotion. You can basically capsulize the whole Romeo And Juliet story in a song, in two minutes. The play lasts for a little longer, but in your life it lasts for on and on and on.

BRESKIN: And yet for all this beauty and joy, your songs are filled with hurt, vulnerability, not just sadness but abandonment.

WONDER: My thing is: the balance of it is what makes it beautiful. You cannot fully appreciate it sometimes unless you know the other side. It would be like a kid who’s always had everything, and then he gets out on his own and says, “Oh, man, what’s happening with this, you don’t know who I am, you don’t know who my family is!!” But if you got a kid with some balance, there won’t be the shock of the world when he gets there. It’s the same with life: you experience joy, you experience sorrow. I mean, the only reason you cry when someone dies is because you know how beautiful it’s been and you know you’re going to miss that emotion. So you cry. You are going to miss something you had in your life.

BRESKIN: Will you in the future rely on the short song-form to deal with all your emotions, or will you work more with extended thematic developments, as in Secret Life Of Plants?

WONDER: I see both. I see going into more intense things, deeper into a lot of different progressions, but I also see doing short songs. All of it, I see all of it. No extended works are in the making right now, but it’s very possible. Very soon.

BRESKIN: One thing that strikes me about your songs, especially the more romantic ones, the ballads, is that there seems to be very little separation — almost none really — between the “I” in the song and you as “Stevie Wonder.” It’s either the conviction with which you sing them, or the fact that they are all truly autobiographical that gives me this feeling, this lack of distance between you and your work.

WONDER: Let’s take the song “Lately.”

BRESKIN: A good example ’cause it’s in the first person — like most of the others — and it’s a tear-jerker.

WONDER: Okay, now it comes from an emotion that was going down that I was feeling for someone else that I thought they might be feeling. You can create that emotion in the lyric as if it were you. Or you can put yourself in that setting — which I usually do — and react to it that way. You may have experienced something enough to already know what it’s about even though it’s not you this time. It’s like often people are explaining things to me and I say, “Yeah, I already know what you mean.” You may have experienced enough to know an emotion, or a color, or a basic mood, or the vibe. What show did you see?

BRESKIN: A few nights ago.

WONDER: Well, we did this song last night from the new album, and I wanted to create this whole vibe. It’s called, “With Each Beat Of My Heart.” So I got them to put a couch on the stage, got some wine, and got a single woman to come up from the audience. And we created the whole mood. Now I’ve experienced that mood before so I know how I want it to be and how to create it.

BRESKIN: You mentioned color. You sang a song the other night with the lyric, “I have the silver in the stars, the gold in the morning sun.” I’m curious as to where your associations come from, your emotive feelings about the colors ….

WONDER: Just from knowing the colors and being told what they’re like, that sort of thing.

BRESKIN: When you think of silver, what comes to mind?

WONDER: Shiny. Flashy. On and off. Spotted.

BRESKIN: You did an all instrumental album way back in the early days, as Eivets Rednow. Do you have thoughts to do something like that again, or something with very little singing?

WONDER: I hope to, yeah. Maybe when I really feel more comfortable with my playing jazz I’ll do that again. (By all accounts, Stevie can throw down improvisational ivory.)

BRESKIN: Do you do a lot of improvising when you’re off on your own?

WONDER: Yeah, yeah. When I’m practicing. On the acoustic.

BRESKIN: Are there jazz musicians ….

WONDER: Chick Corea I like. Art Tatum, man, as you know, is ridiculous. Keith Jarrett, a great player. Improvisations, I’m telling you. How was it to interview him?

BRESKIN: Everybody told me that I wouldn’t like him, that he was a real S.O.B., but he was very straight about it. Gave it a lot of time and thought, was quite receptive. You hear so many things ….

WONDER: About me and about everybody else. You got to find out for yourself … I think we should continue this on the phone. I’m feeling kind of strange. I need to cool out for a second.

■

As requested, I gave Stevie my phone number and he told me he’d call me the next day. Dream. Over the next four weeks, I spent so much time with the phone with his publicist, Ira Tucker, Jr., that we thought we’d run an interview with Ira instead of Stevie. Ira continually tried to get Stevie back to me. One day, his secretary called around noon and told me to “Get ready, Stevie’s gonna call within the hour.” I wait seven hours. I finally call Ira and ask his permission to go out to dinner (feel like a grounded teenager) and he says, “Don’t wait around man, go.” Come back to the apartment and here’s a message from Steveland Morris on ye olde phone machine, saying he’d call back in two hours. Dream.

Two days later, I get a call from Ira saying Stevie’s gonna call. Stevie calls, saying he’s got family business now but he’ll call at 11:00 tonight. At 10:45, it’s Stevie in an airport saying, “I got to introduce you to another reality.” “Too much reality,” sayeth I. “Got to have it, man,” sayeth Stevie, “Got to have it, bay-beah. Listen, I’m in Cincinnati. I’m on my way to L.A. Listen, so what I’m gonna do is call you 9:00 my time, 12:00 noon your time tomorrow. I just wanted to let you know what was happening.” I wait eight hours. No call. After another week and a half of this, Ira finally calls to say Stevie’s sorry about all this and he’ll call tomorrow, to do nothing else if not apologize (he doesn’t).

Now the only reason anyone (meaning myself) would put up with all this is because Stevie Wonder matters. He matters not only because he is quite probably our greatest writer of the popular song, but because his vision embraces more than either the silly love song or the party rap — both of which he’s also good at. In an age of song so bereft of political or social integrity that Prince’s escapist fantasy, “We’re gonna party like it’s 1999,” can be taken as the heaviest black pop statement of the year, Stevie Wonder matters all the more. He packages his ideas smoothly: living the myth of the Blind Seer, he subverts the status quo with melodic confection that gives you something to think about when the party’s over as well as a serious party. (And by the way, folks, if you think plants are undeserving topic for a double album, try breathing without them.)

Stevie’s rudeness in failing to finish the interview cannot be excused (and he wouldn’t excuse it himself); it may, however, be explained. The man is surrounded — not by the enemy — but by his own people. And as Lennon remarked, it’s the courtiers that kill the king. Stevie Wonder employs roughly a hundred people — musicians, technicians, family members, administrators, managers, publishers, packagers, talent developers, stagers, secretaries, sycophants — and he may be feeling a little uneasy in the saddle these days. He is the president of his own publishing company, his own studio, his own radio station (KJLH) and his own Motown-distributed label, Wondirection, for whom he produces records. He is also a husband and a father, a man dedicated to his family. He also also has comedic aspirations and he has also also also aspirations for world peace. When it’s cold outside, Stevie Wonder does not exactly have the month of May.

In addition, he may be suffering from “The Thriller Effect.” Or: where do you go creatively and commercially after Michael Jackson has just done something like twenty million copies? Wonder has always had difficulty parting with new material, and the wide-open vista for black pop in Thriller’s wake cannot be making his creative decisions any easier. He would clearly like a record that big.

This week — in the middle of a stop-and-go tour — he dumped his entire band, some of whom have been with him for years. Under Stevie’s own brand of high-finance humanitarianism, he will continue to pay them not to play for him. He has had to cancel gigs and he is still in the studio tinkering with the new record and rehearsing his new group. So the big question of the Christmas season becomes (drumroll please): how will Stevie Wonder play Richard Pryor to Michael Jackson’s Eddie Murphy?